Book review: The Anxious Generation

April 01, 2025; Updated April 02, 2025

Vaden and I dedicate episodes 82 and 83 to this topic. This review is based on our discussion, but contains much more info than we could provide in audio format without boring the listeners to death. As always, if you find any mistakes let me know and I’ll correct them.

The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt is not a good book. Sorry.

I’m tempted to end the review there but, alas, I cannot get away with that because I’m not Tyler Cowen. Instead, I’m going to treat you to 7,000 words of excruciating detail on what makes it a bad book.

But for those of you who will only read the introduction, here’s my argument in a nutshell: It’s a bad book because it radically oversimplifies what should be a nuanced conversation about certain mental health trends among adolescents.

Had the book done its job, a reader would come away with an informed picture of what the literature says on this topic. Instead, an unwary reader will emerge from the book with a wildly distorted view of the academic conversation about this question. You won’t know about the data sets that conflict with Haidt’s claims, you won’t know how many studies question his findings, you won’t know how difficult it is to even study causation in this setting, or of the many issues plaguing the studies that attempt to do so. You certainly won’t know about effect sizes, or correlation coefficients, or alternative hypotheses that explain the data. You will not be well-prepared to have informed conversations with your children about social media.

Am I saying that all books must be nuanced, careful, and academic? Must they be dry and technical, talk about statistical models, sample sizes, demand effects, and confounders? Yes, I suppose I am saying that. Or, at least, books claiming to weigh in on an important public health question (and suggest government intervention based on their conclusions!) should be held to a higher standard than regular popular science books. Nobody demanded that Haidt write this book. He chose to write it because he feels strongly about his thesis, but that doesn’t permit him to oversimplify the literature to suit his needs.

My annoyance is directed towards The Anxious Generation in particular, not Haidt in general. Outside of the book, he’s treating his thesis how we should want any social scientist to treat their favorite ideas: By soliciting feedback, being transparent with data, and engaging with critics. Haidt’s substack does this well, and he and his co-authors have open-sourced their literature reviews—a rare move in the social sciences.

I also respect Haidt for other reasons. He has been an admirably consistent voice in the fight for free speech on college campuses, sounding an early alarm about the rise of illiberalism along with Greg Lukianoff in the The Coddling of the American Mind. He founded Heterodox Academy with the goal of protecting open inquiry and increasing viewpoint diversity in what has become a left-wing silo. And he co-founded Let Grow, which encourages resilience and self-reliance in kids.

But I think Haidt’s conclusions in The Anxious Generation are premature, and that his book is likely to do more harm than good.

I. What’s the problem?

Haidt’s claim is that there is a severe decline in the mental health of adolescents—particularly adolescent girls—and that social media is a major cause of this decline. I think he’s correct about the decline (at least, in some parts of the world) but I’m skeptical that we know enough to attribute the decline to social media. But let’s first look at evidence for the decline itself.

The first thing Haidt looks at is self-reported rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. You should pay attention to these rates, but not anchor on them too closely. Reported rates can increase for many reasons beside an actual increase in anxiety and depression. There might be less stigma around discussing mental-health, less stigma about seeking help, evolving diagnostic categories, an increased willingness to diagnose anxiety among therapists, or an increase in social status accompanying poor mental health.

The more important metric is self-harm and suicide rates. Are reported rates of anxiety translating to more girls and boys showing up in morgues and hospitals? If so, we have a real problem on our hands.

I.I. Self-harm rates

Sadly, self-harm rates do appear to be increasing in various countries, and the increases typically started around 2011-2012. As Haidt points out, this is roughly when we should expect to see social media start to have an effect on mental health if his thesis is true. The smartphone was introduced in 2007, Facebook in 2006 (for the public), Instagram in 2010, and Snapchat in 2011. But before the 2010s, it was rare for teenagers to have access to social media on their phone. In 2011, less than a quarter (23%) of teenagers (ages 12-17) had a smartphone. In 2015, 73% did. In 2016, 79% did. Haidt calls the period between 2011 and 2015 “the great rewiring,” because adolescents were spending more of their childhoods on their phones.

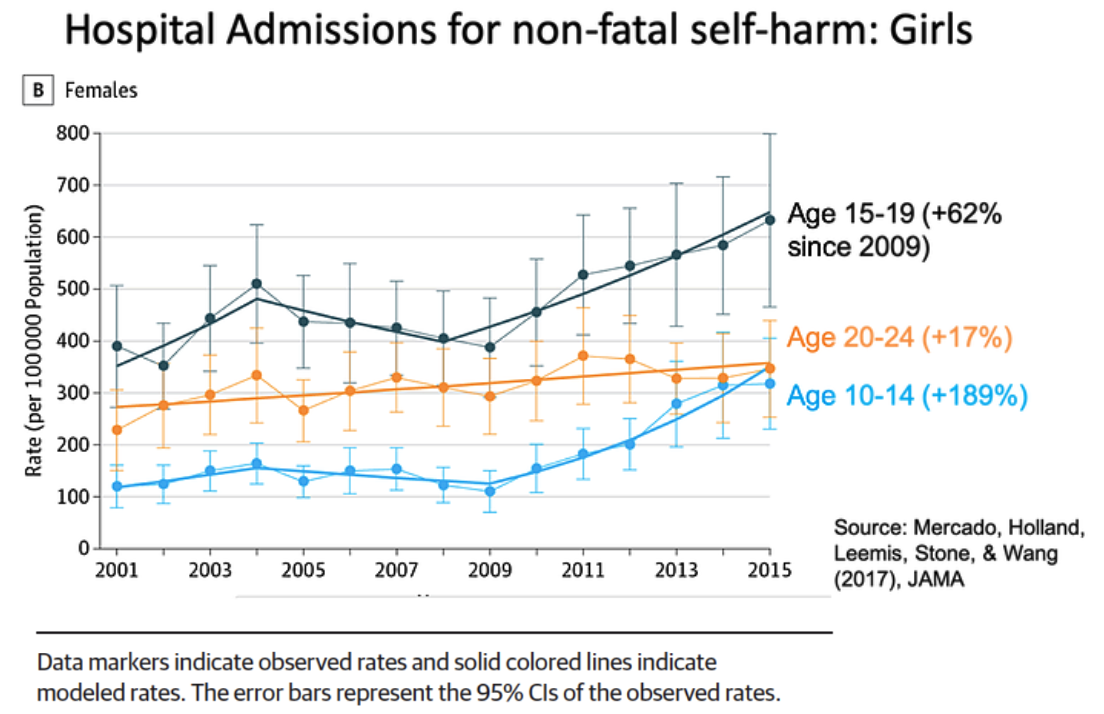

Here is the data for self-harm rates among adolescents girls in the US:

Data source. Labels added by Haidt, see Section 2 here.

Haidt does not present this plot in the book. He presents only the data for girls aged 10-14 (this is where the often-quoted 189% increase comes from1). Now, clearly, something seems to be happening with girls aged 10-14 and 15-19, starting around 2010. But the increase is less among those aged 15-19 (62% instead of 189%). This is notable because 15-19 year olds are more likely to have phones than 10-14 year olds. This would seem to pose a problem for Haidt—if those adolescents more likely to own phones are seeing less of an increase in self-harm rates, are we sure it’s the phones? Unfortunately, Haidt does not discuss these data in the book, so we’re left unsure what his explanation is. He is aware of the data, however, since I got this plot from Section 2 in his collaborative review doc.

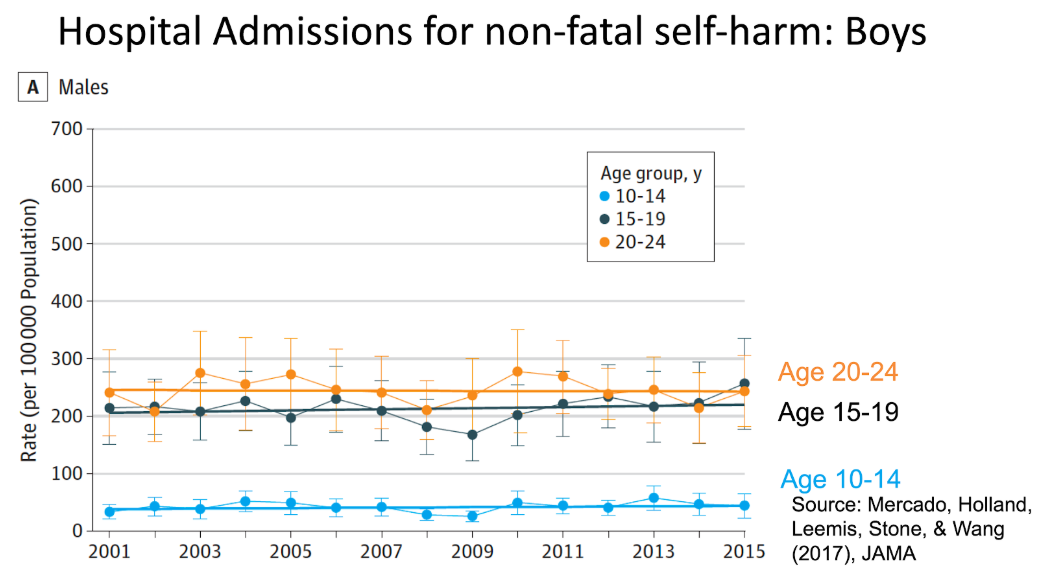

Meanwhile, boys in the US are not undergoing any significant increases in non-fatal self-harm rates:

Haidt acknowledges that the story for boys is more complicated. But he also doesn’t present this data in the book, presumably because it’s undermining his case. It’s important to keep this in the back of your head, especially when Haidt begins advocating severe, government-led restrictions on all adolescent screen time.

Let’s take a moment to put the scale of the problem into perspective. Among 10-14 year old girls, hospital admissions for non-fatal self-harm increased from an average of 100/100,000 in 2010 to roughly 300/100,000 in 2015. This is indeed a big increase percentage wise, but as Vaden points out in our episode, it’s important to keep the absolute scale in your mind as well. In a high-school class of 2,000, half of them girls, the increase represents one girl in the ER a year versus three girls a year. Obviously, we should be concerned about any teenage girls in the ER, but when deciding on public policy we need to be clear and honest about the size of the problem.

Still, a small increase in the number of girls who legitimately hurt themselves signals a larger increase in the number of girls who are anxious or depressed, but who won’t self-harm. And that’s concerning.

How are other countries doing? The internet and smartphones were both widespread across the western world by 2010, so we should expect to see similar increases across the anglosphere. And in some countries, we do.

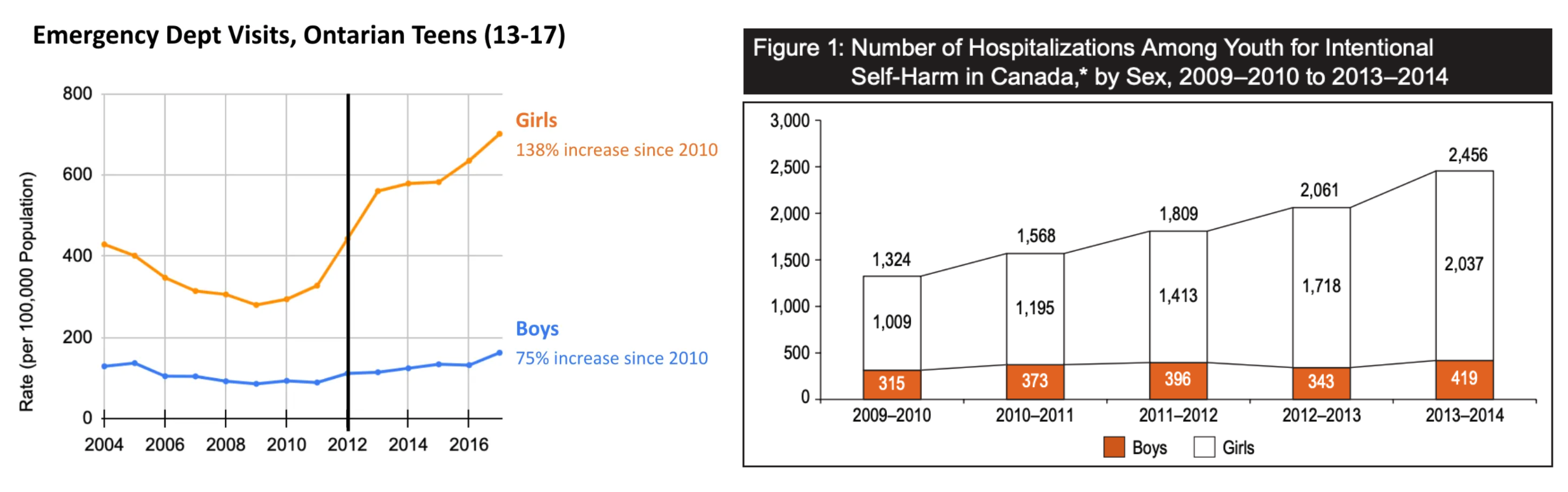

Here’s the case in Canada (Ontario contains 40% of Canada’s population. The left figure is what Haidt presents in his substack, the right corroborates the general trend in the rest of Canada—excluding Quebec—from 2009-2014):

Left: Data from Canadian National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS) data. Data originally plotted in Gardner et al. (2019). Right: From the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

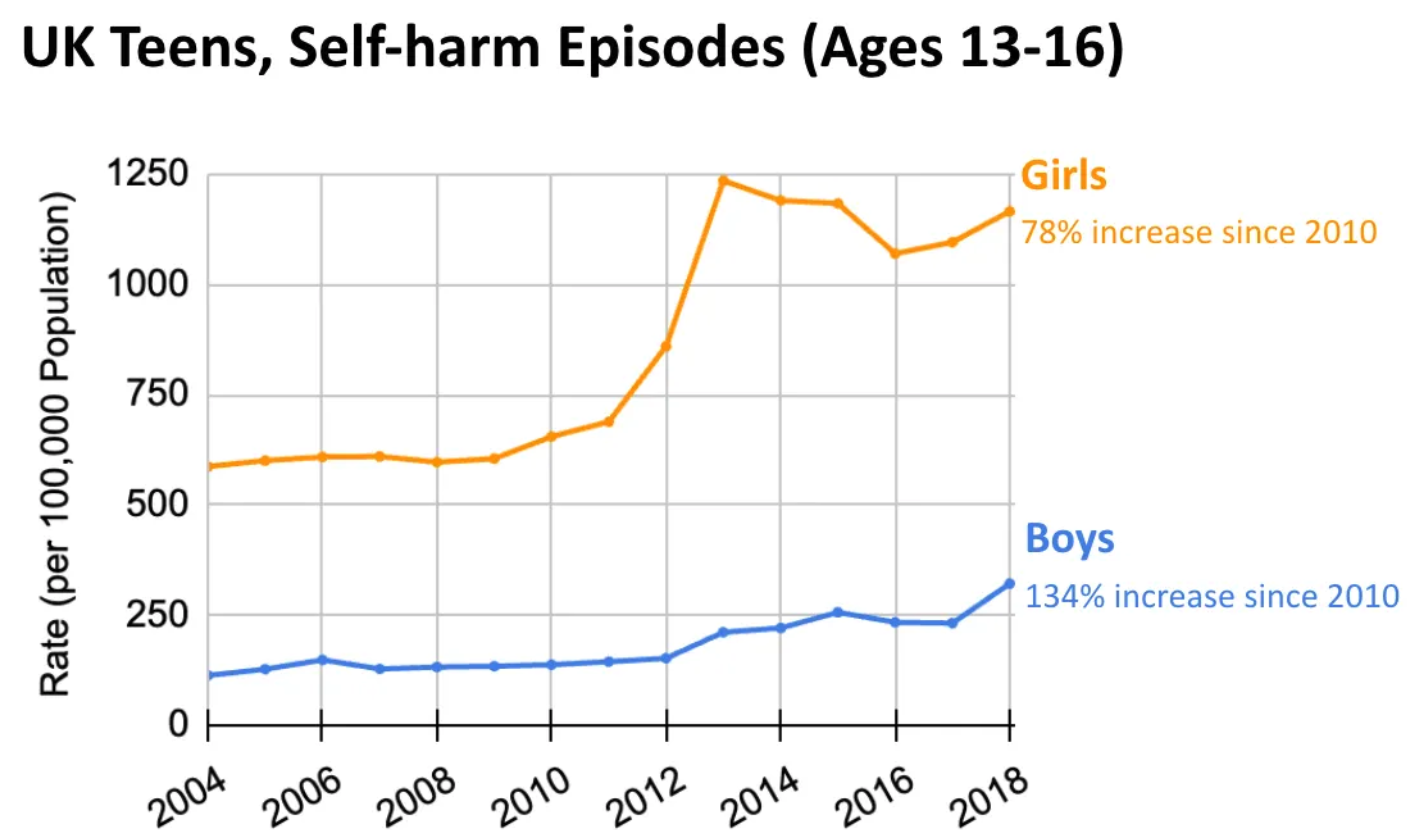

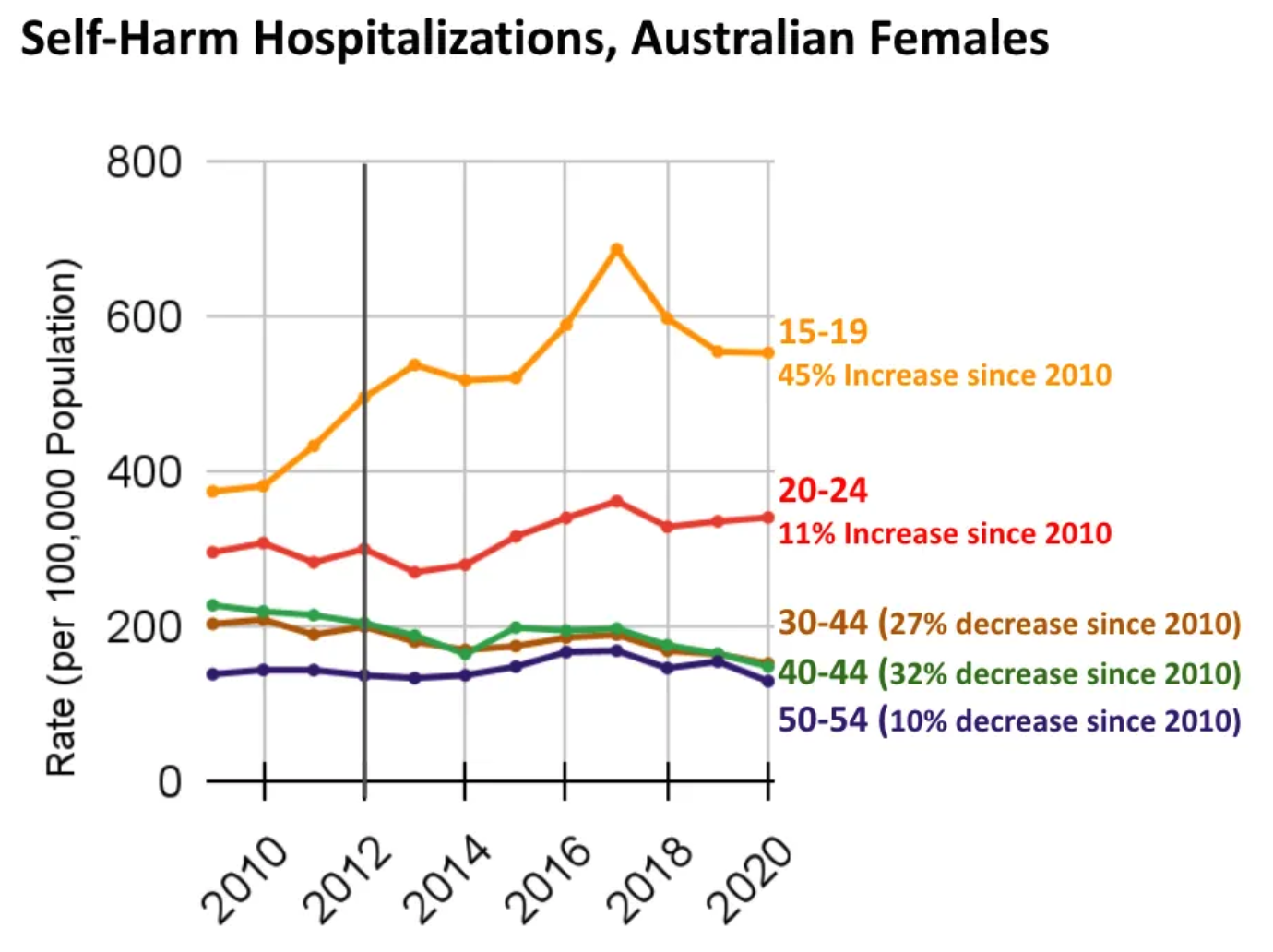

And here’s the UK and Australia. The data for the UK is not self-harm based on hospital admittances, but instead based on primary care records (I’m not going to pretend to know if this makes a big difference or not). Both of these plots are from Haidt’s substack; he only presents the UK data in the book.

Aurum and GOLD datasets of the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Originally plotted by Cybulski et al (2021).

Data from 2019–20 National Hospital Morbidity Database—Intentional self-harm hospitalizations.

So yes, there is a common trend across several countries. Namely, from 2010-2015, non-fatal self-harm rates increased among adolescent women (and in two of the four countries, also among adolescent men, but by significantly less).

But it’s also important to notice that while the rise from 2011-2015 is similar across these countries, the post-2015 trend varies. The basic logic of Haidt’s thesis, however, would suggest that self-harm rates should continue increasing post-2015. After all, the number of teens with smartphones kept increasing. In the US, in 2022, 95% of teens had smartphones, up from 79% in 2016. And social media didn’t stop developing. Tiktok was introduced in 2016, after which other platforms also introduced “shorts” (short-form vertical video) to compete. If anything, social media got more addictive post-2015.

On Haidt’s view, more social media is consistent with the continued rise of self-harm hospitalizations in the US. But what about Australia? The number of phones has continued to increase (91% of teens have their own smartphone as of 2023), but self-harm rates decreased from 2017-2020 among females 15-19 and 20-24 years old.

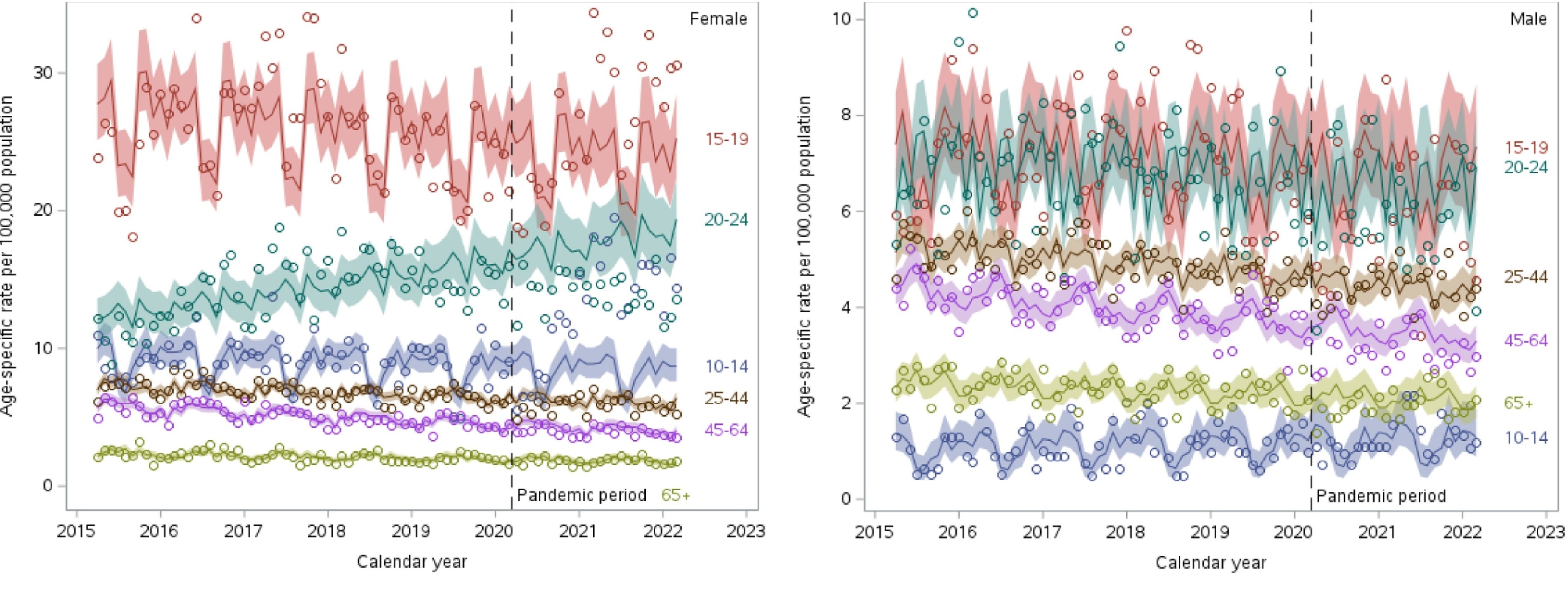

Canada’s post 2015 trend is also inconsistent with Haidt’s thesis. The only increase appears to be among 20-24 year old women—10-14 year olds and 15-19 year olds have consistent or decreasing rates of self-harm. (The vertical line is the onset of Covid, which is what the authors here were interested in.)

Self-harm hospitalizations by age-group in Canada in all provinces except Quebec. Circles are the data, line and shaded areas are model predictions. Try and ignore the lines if you can and focus on the circles. Source.

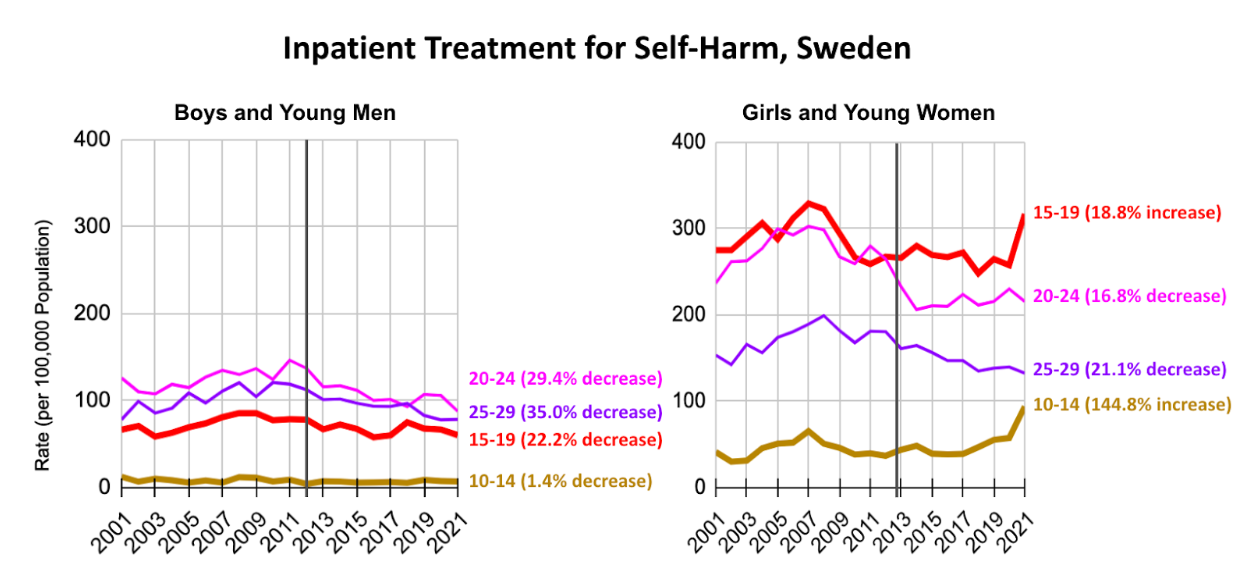

Ok, so we’ve seen increasing self-harm rates in several countries, especially in the 2011-2015 period. Are self-harm rates increasing in 2011-2015 everywhere? No. Here’s data from Sweden.

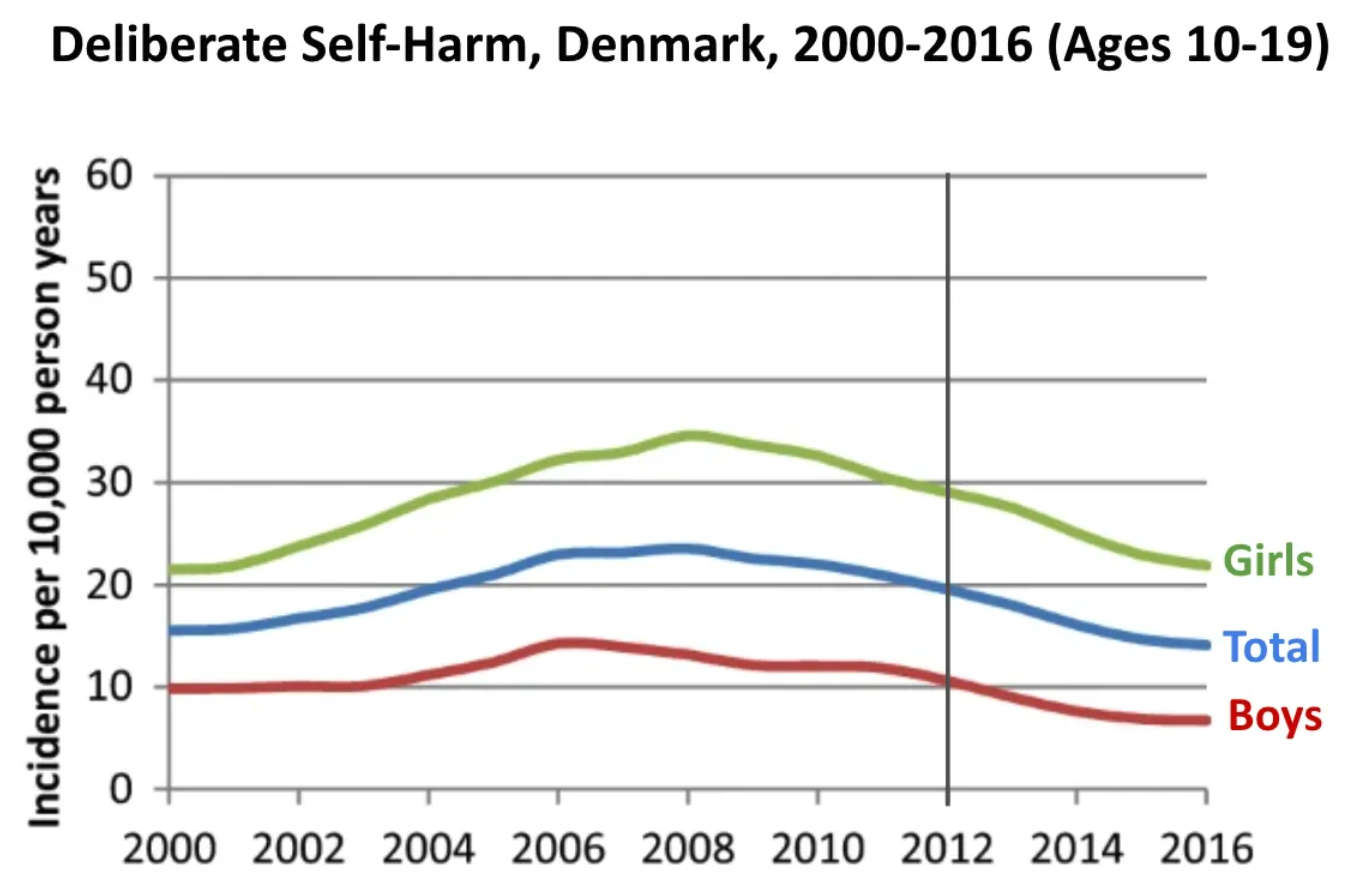

There is an uptick for girls aged 10-14 and 15-19, but it occurs well after 2015. If I had to guess, I would assume it was a spike from Covid-19. Here’s data from Denmark:

Source (Section 6).

There are some subtleties here. In particular, one thesis for the decrease in Denmark is that they implemented policies to restrict the supply of over-the-counter analgesics. But Haidt does not discuss this in the book. It’s buried deep in his substack, where anxious parents with children are less likely to look.

I.II. Suicide rates

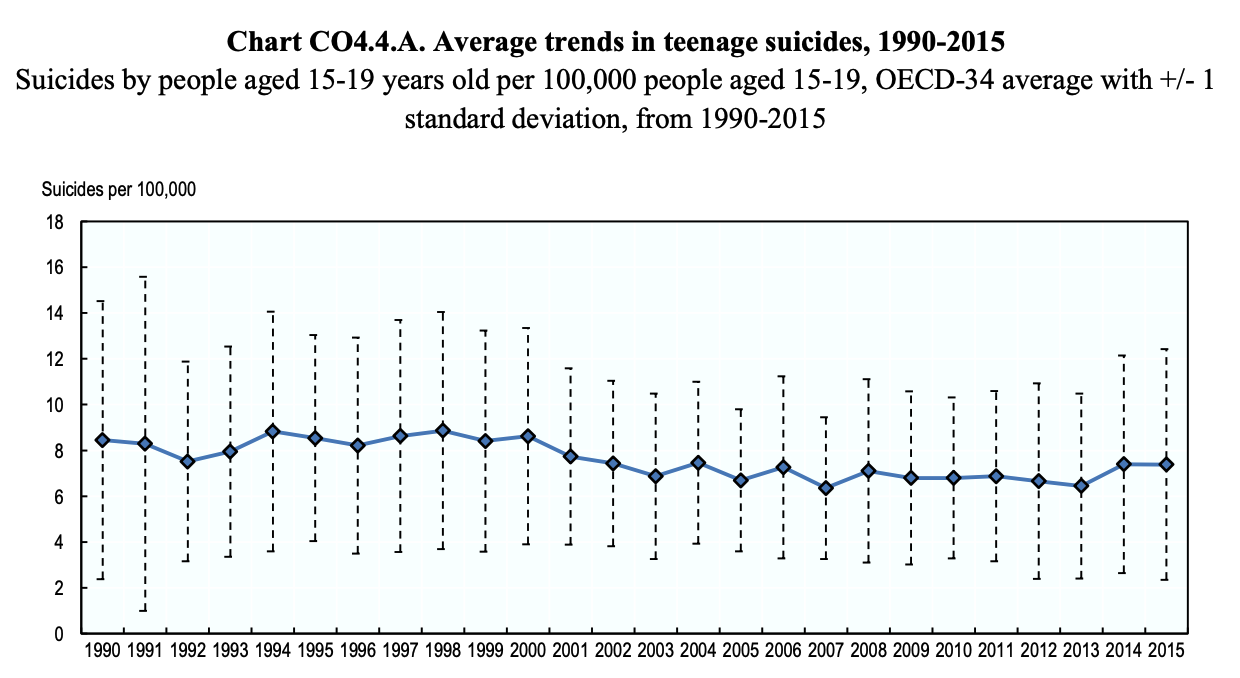

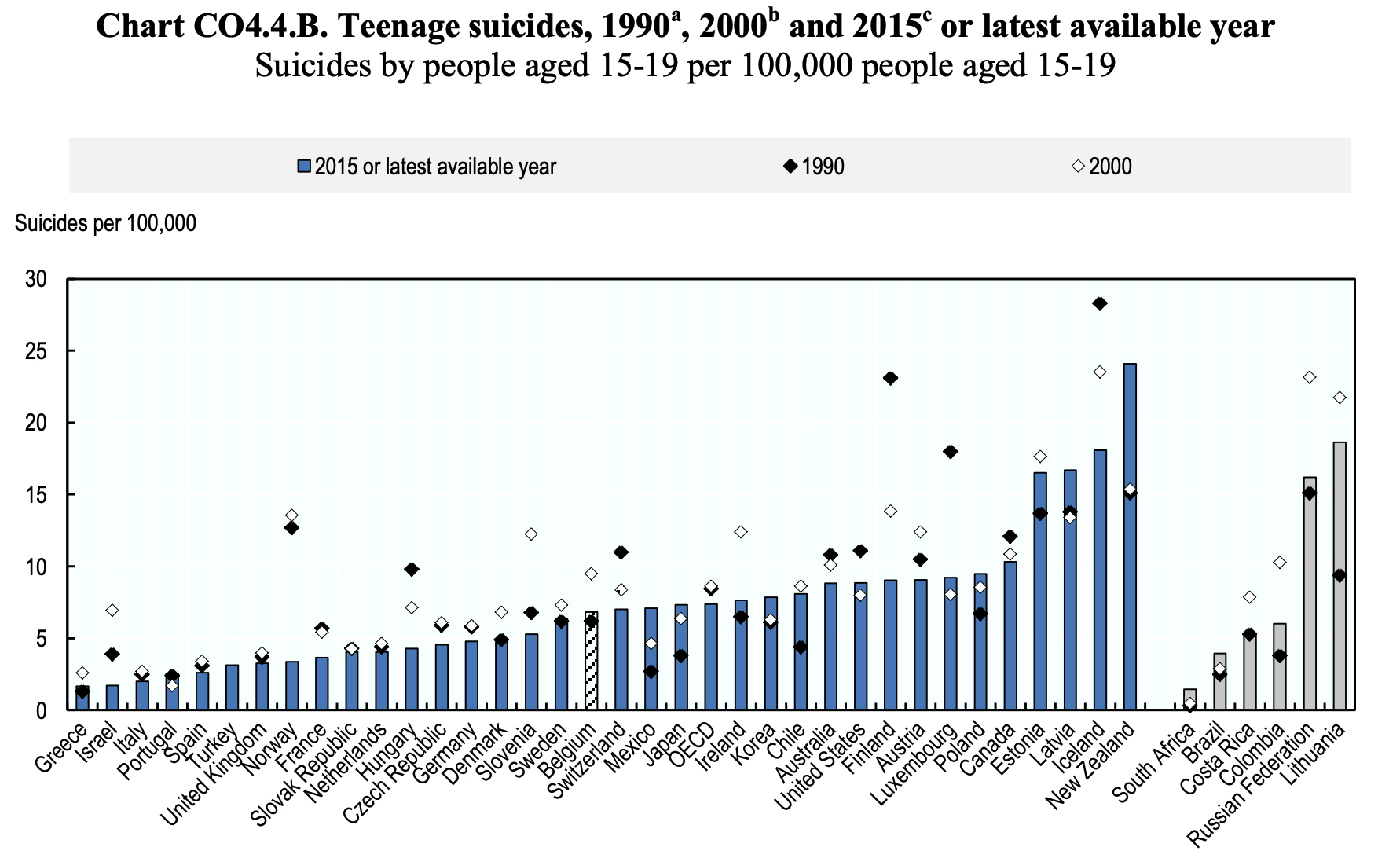

Do these increasing self-harm rates lead to increasing suicides? Not in OECD countries at large:

Data from the WHO See this report for these specific graphs.

In fact, for many countries, suicides in 2015 among 15-19 year olds is less than it was in 2000. (Caveat: for some of these countries the latest year available is ridiculous long ago. See footnote (c) in the report for specifics.)

Same data as above.

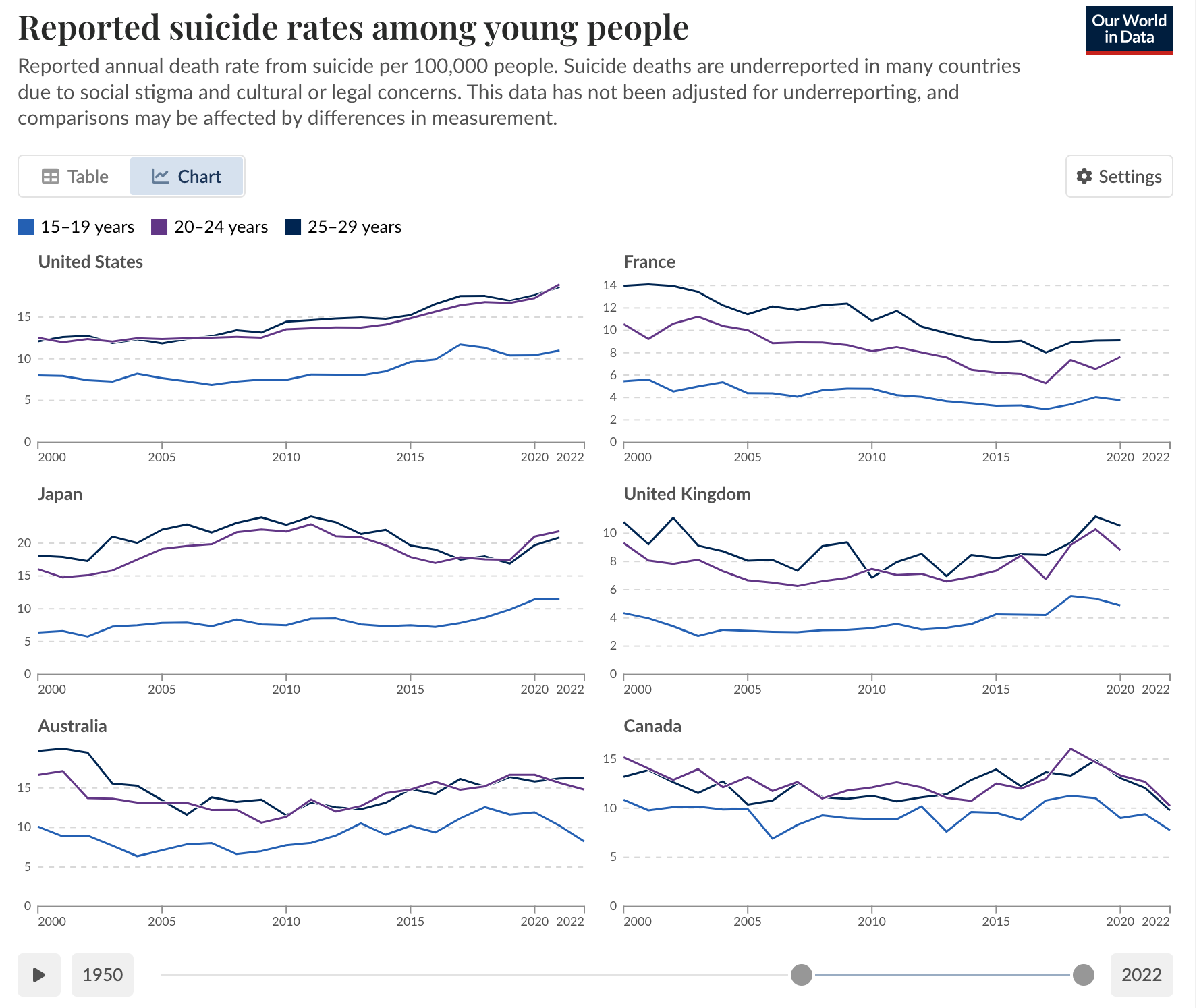

Here are suicide rates for US, France, Japan, UK, Australia, and Canada, from 2000-2022. The US, Japan, and the UK saw an overall increase in suicide rates among 15-19 year olds, while Australia, Canada, and France saw no change or a decrease. Moreover, in the US, Japan, and the UK, suicide rates rose among all age groups, not just adolescents.

Plotted by Our World in Data. Data from the WHO.

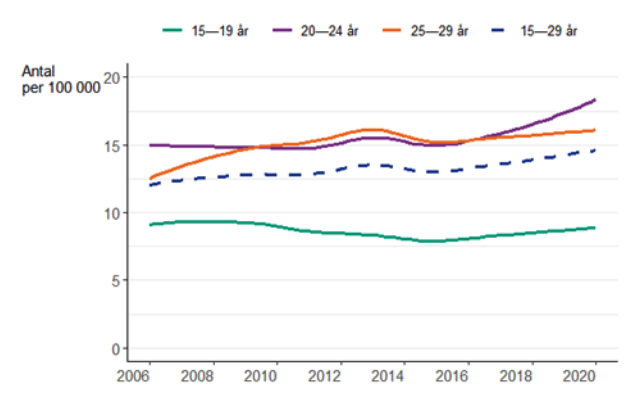

In Sweden, suicide rates have decreased from 2006 to 2020 among 15-19 year olds, but increased for other age groups (Figure is in Swedish, sorry. But if you can’t read Swedish by now what are you doing? It’s the lingua Franca of the best looking people on the planet for God’s sake):

Data from here.

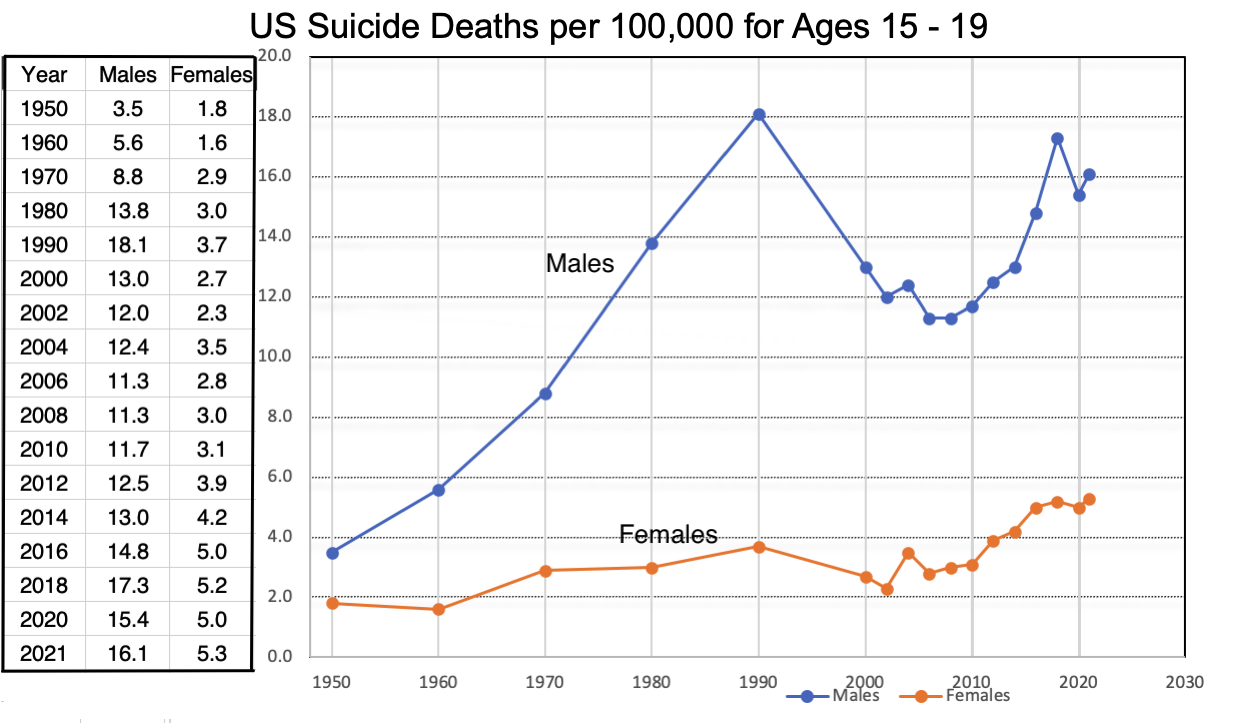

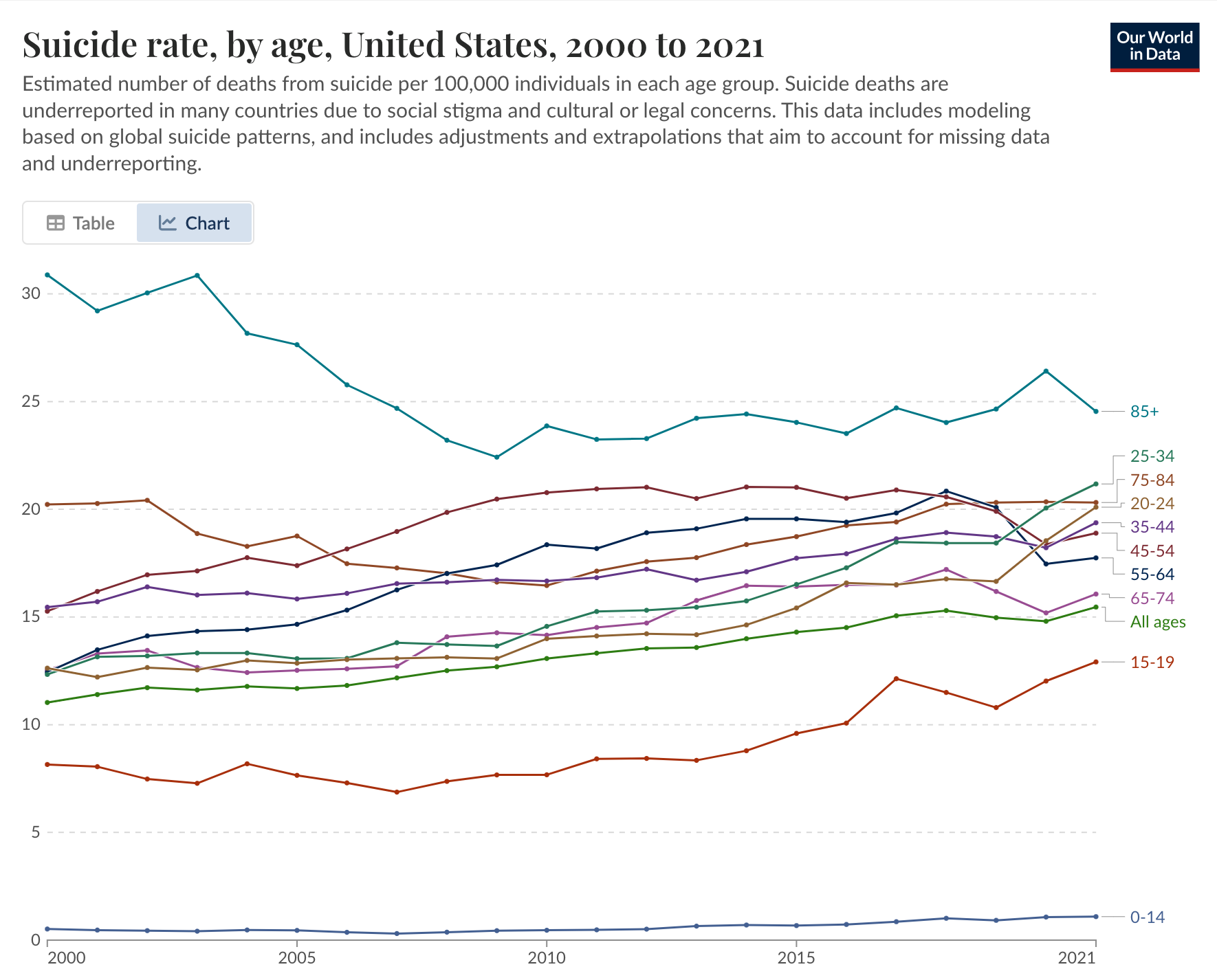

Finally, let’s return to the US. There is an increase in suicide rates among teens in the US. The rise is considerably more drastic for males than females:

Data compiled from here for 1950-2001, and from here from 2001 onwards. Plotted by Peter Gray in his substack post.

Another important piece of context is that suicide rates have been increasing for almost all age groups in the US. This is tragic, but recall that Haidt’s thesis is that social media is uniquely bad for adolescents. If suicide is increasing among all age groups, it suggests that there might be a common cause.

Plotted by Our World in Data. Data from the WHO.

I.III. Summarizing the morass

Where does all the data leave us? There does seem to be a precipitous rise in self-harm rates from 2011-2015, and to a lesser extent suicide rates, in several countries. The rise started roughly at the same time, and it seems too consistent to be random noise. There is something in need of explanation here.

However, there are clearly some data which contradict his view. For one, there are countries in which self-harm rates are decreasing. Second, the rise stops in many countries after 2015, which is possibly inconsistent with Haidt’s thesis (though we wouldn’t know, because we’re not told what his thesis predicts specifically). Third, the rise in suicide is only in select countries.

Disappointingly, the book does nothing to explore these complexities. It leaves readers with the impression that wherever data exists, we see this rise. Moreover, it deliberately sweeps various complexities under the rug. It uses data for 10-14 year olds when convenient, and data for 15-19 year olds otherwise. Later in the book Haidt will justify his conclusions with experiments done on college students, i.e., 18-25 year olds. This lack of nuance and attention to detail is frustrating, to say the least.

II. Haidt’s thesis

But let’s give Haidt the benefit of the doubt about these trends. What’s his explanation?

There are developmentally sensitive times of childhood—times when our brains are uniquely primed for socializing and learning. This has a well-known evolutionary logic: unlike other animals, our brains are not fully wired up before birth because we have much more learning to do during childhood.

We spend these formative years playing and socializing in order to learn about our environments and how to productively interact with adults and other children. Haidt claims that social media has hijacked this learning process. We’ve moved our developmentally sensitive years to our phones and this, in his view, is a disaster. He calls this “the great rewiring”.

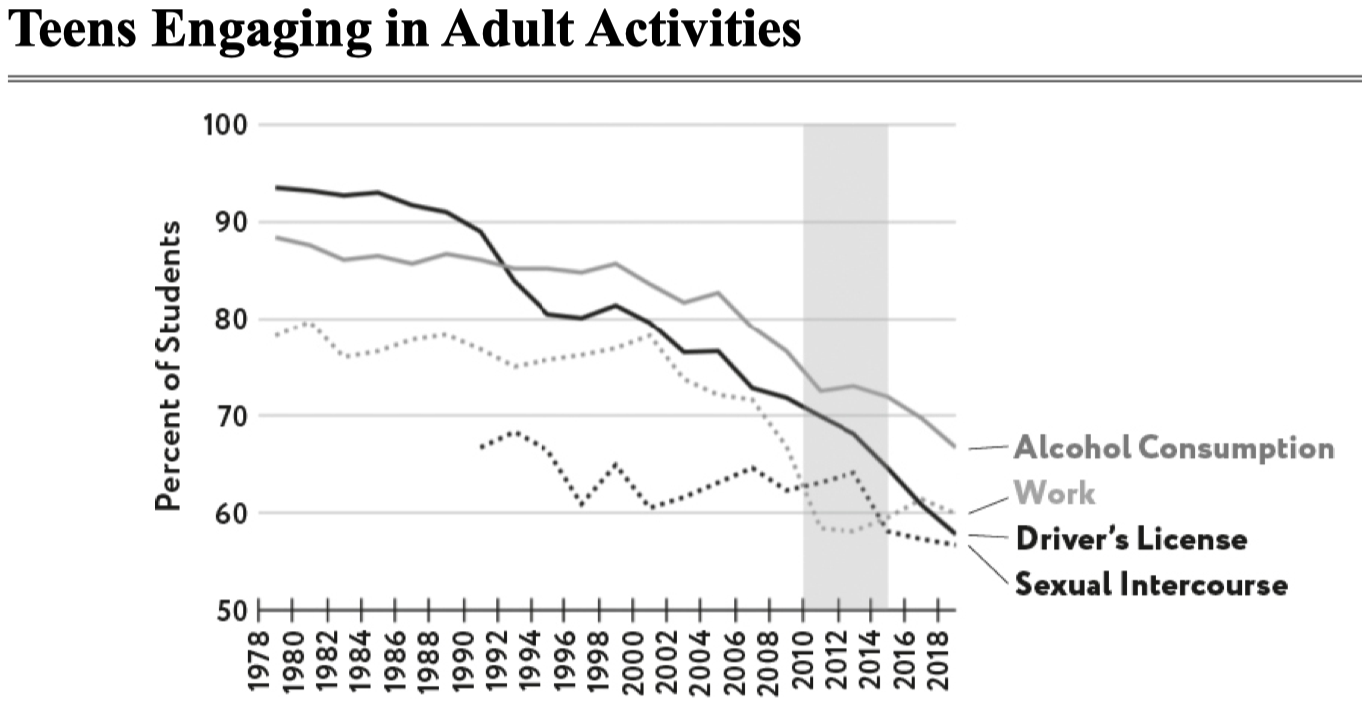

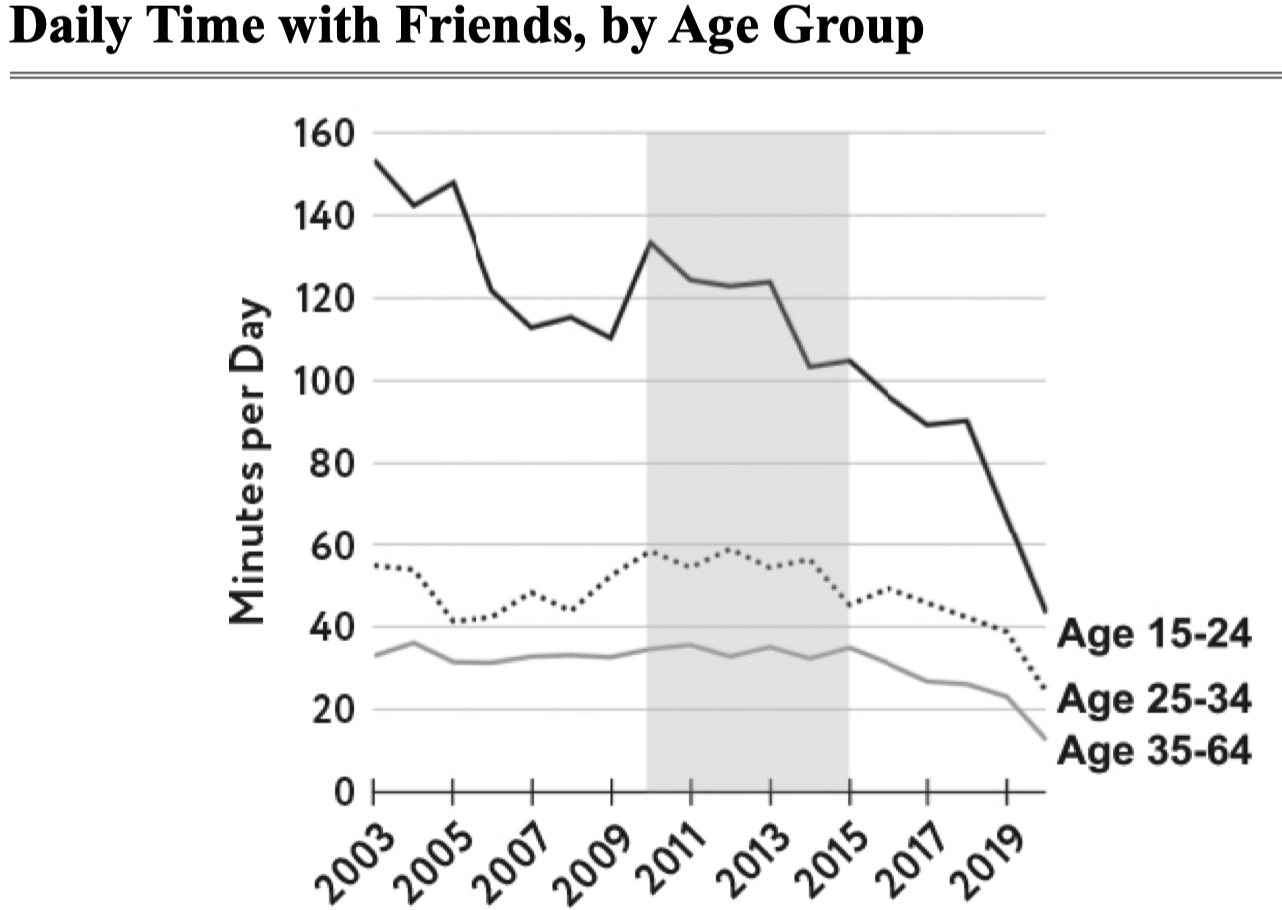

To Haidt’s credit, how teenagers are spending their time does seem to be changing:

Figure 4.1 in The Anxious Generation.

Figure 5.1 in The Anxious Generation.

Of course, it’s unclear whether these trends are bad and it’s especially unclear whether they’re caused by social media.

Haidt gives a variety of explanations for why social media in particular is detrimental to our mental health. He discusses social deprivation, sleep deprivation, attention fragmentation, and addiction. He claims that social media disrupts our natural process of social attunement, whereby we learn how to navigate relationships and social norms. He claims that social media disrupts our ability to learn from those we need to (teachers, community members), and instead has us copying influencers. He claims social media keeps us in “defense mode” instead of “discover mode,” making us wary of the real world and afraid to take on challenges, navigate risk, and be agentic.

These explanations all sound good if you’re already convinced that social media is causing harm. But the more skeptical you are, the weaker they sound. Is it bad to have kids learning from people on the internet rather than people in their immediate communities? You can interact with many more theoretical physicists, chess grandmasters, professional dancers, and standup comedians online than you can in person.

In other words, it’s easy to come up with any post-hoc story you like to explain the rise in self-harm rates. Explanations are easy; the point of statistics is to stress test our cherished ideas so that we don’t fool ourselves. Haidt’s case rests on whether he can show a causal connection between social media and mental health.

And here we get to the major issue I have with The Anxious Generation. The section discussing evidence of correlation and causation, which are the data needed to substantiate his points, takes up all of five pages. Five pages! The book is over 400 pages long and waxes lyrical about the spiritual degradation we sustain as a result of social media, the four foundational harms, and how we as a society can solve this urgent collection action problem. I don’t know whether to be enraged or impressed with Haidt’s chutzpah here. I would not have the nerve to write a several hundred page book calling for significant government intervention while summoning only five pages of statistical evidence.

To make matters worse, the evidence is weak! The data quality is poor, the studies are flawed, and researchers are divided (in fact, I’d go so far as to say that most researchers in this area disagree with Haidt—see below). Would you know of any of this after reading the book? No, you’d be convinced that Haidt is standing on a rock-solid mountain of evidence.

II.I. Is anxiety/depression correlated with social media use?

First up: is there a relationship between social media and poor mental health? We’re not asking about causation yet. We’re simply looking at whether social media is associated with poor mental health outcomes. (An association, if found, could be due to causation in either direction, or to some third variable which causes an increase in both.)

A note to the reader: Haidt’s argument depends on establishing a causal link between social media and mental health. If that’s your primary concern, you might consider skipping this section. But correlation is still worth examining for at least two reasons. First, a robust correlation suggests there’s something potentially worth studying causally—it acts as a “signal” in the noise. Second, correlation coefficients (and particularly \(r^2\)) can tell us how much of the variance in mental health outcomes is associated with social media use. Even if we later establish a causal link, understanding this variance is useful for questions of public policy.2

Haidt’s claim is that the size of the correlation between social media use and “internalizing disorders” (i.e., poor mental health) is roughly \(r=0.2\) for girls. Here \(r\) is “Pearson’s correlation coefficient” and runs from -1 (perfect anti-correlation) to 1 (perfect correlation).

He writes the following in footnote 7 of Chapter 6:

Jean Twenge and I have found [the correlation] to be around \(r=0.20\) when you limit the analysis to girls and social media. Orben & Przybylski (2019) said that the correlation was equivalent to \(r < 0.04\), which truly would be negligible, but again, that was for all digital activities and all teens. When Amy Orben (2020) reviewed many other studies that were limited to social media (rather than all digital media), she found that the associations with well-being range from r = 0.10 to \(r = 0.15\), and that was for boys and girls combined. The effects are usually larger for girls, so that puts it up above \(r = 0.15\) for the link between social media and poor mental health for girls, which is very close to what Twenge and I have found. … So the research community is closing in on a consensus that crude measures of social media use are correlated with crude measures of anxiety and depression, for girls, at a level around or above \(r = 0.15\).

I think this is a mostly accurate summary of a general trend in the literature. There seem to be many studies that don’t find a significant association when you look at the effects for men and women combined. But when you focus in on adolescent women in particular, there is often an association of somewhere between \(r=0.05\) to \(r=0.2\) (though the highest I’ve ever seen is \(r=0.2\); it’s usually more like \(r=0.1\) to \(r=0.15.\) I find it annoying that Haidt keeps using 0.2 as some sort of standard. ) For example, this seems to be the case for the Valkenburg et al. study, which is a study you’ll often see thrown around by people who want to discredit Haidt’s thesis. (Haidt’s discussion of this study is on page 375 here.)

There are a few things to say about this finding.

First, this is the association between social media use and reported mental health measures. This is not self-harm or suicide. I don’t know where those data are, but I’d like to see them.

Second, if there’s no association when we look at both girls and boys together, then the effect is nowhere near as severe for boys alone. This is consistent with the data we saw above. To his credit, Haidt acknowledges in the book that the effect of social media is more complicated for boys. He writes “[m]y story is more speculative than the one I told about girls in the previous chapter because we just don’t know as much about what’s happening to boys.” (pg 189). However, he rarely acknowledges this caveat when discussing his thesis in public. And his policy proposals do not take into account that the effect for boys is often non-existent.

Third, and somewhat technically, we should note that these correlation coefficients assume a linear relationship between the two variables. If, say, the response is quadratic in the covariates (eg \(Y=X^2\)), then \(r\) will underestimate the strength of the relationship. So if mental health gets worse super-linearly (i.e., more than linearly) with social media use, \(r\) will not capture the strength of that correlation.

Fourth, it’s important to recognize that there is still disagreement here. We shouldn’t think that \(r=0.15\) is the end of the story for girls. Plenty of studies find almost no correlation (e.g., here). Further, in his substack post (written before The Anxious Generation), he notes that analysis decisions can have a huge impact on the findings:

There was one other difference that turned out to make a large difference in our results. Orben and Przybylski had not only controlled for demographic variables (such as race and parents’ educational levels, which is universally done); they also controlled for some psychological variables that are potential mediators of a relationship between social media usage and poor mental health, such as negative attitudes about school and closeness with parents. We found that controlling for these psychological variables heavily suppressed the relationship between social media use and poor mental health.

Finally, let’s assume Haidt is right (Haidt makes right!). Is \(r=0.15\) substantial? Depends on what we’re studying. In fairness to Haidt, it’s high enough to sometimes warrant public policy changes in other domains. In one of the collaborative review docs he writes:

For example, Gotz et al. note that the correlation of calcium intake and bone mass in pre-menopausal women is \(r = .08\), which is enough to recommend that women take calcium supplements. The correlation between childhood lead exposure and adult IQ is \(r = .11\), which is enough to justify a national campaign to remove lead from water supplies.

He continues:

So is a correlation coefficient of .15, or .20, between a behavior and a health outcome “small potatoes”? Is it so small that it has no implications for public policy? No. In the Millennium Cohort Study, the correlation of well-being with social media use, for girls, is around .19. This is about the same as the correlation of well being with heroin use for boys (.19), and it is larger than the correlations of well-being with many known health-related behaviors for girls, including heroin use (.10), and exercise (.06).

Okay, so where are we at? I’m ready to believe there’s an association of somewhere between 0.1 and 0.2 for girls. I’m not ready to believe we have consistent correlation for boys, despite Haidt claiming so in several places. But the data are extremely messy, and most of the studies are bad. In fact, researchers in this area have written papers talking about how bad the data are. For instance, Odgers and Jensen (2020) and Orben (2020) . We’ll revisit their criticisms later.

Let’s move onto causation.

I.II. Causation part 1: Dose response-studies

There are several ways to study causation for this question: dose-response studies and natural experiments.

Dose-response studies look for effects at the individual level. These ask people to change the amount of time spent on social media (the dose) and then monitor their anxiety and depression levels (response). If the participants were randomly assigned, and if the group spending less time on social media is less anxious, we conclude that social media is a cause of increased anxiety.

Here’s the entire paragraph devoted to dose-response studies in Haidt’s book:

[O]ne study randomly assigned college students to greatly reduce the use of social media platforms (or not reduce, for the control group) and then measured their depressive symptoms three weeks later. The authors reported that “the limited use group showed significant reductions in loneliness and depression over three weeks compared to the control group.” Another study randomly assigned teen girls to be exposed to selfies taken from Instagram, either in their original state or after modification by the experimenters to be extra attractive. “Results showed that exposure to manipulated Instagram photos directly led to lower body image.” Taken as a whole, the dozens of experiments that Jean Twenge, Zach Rausch, and I have collected confirm and extend the patterns found in the correlational studies: Social media use is a cause of anxiety, depression, and other ailments, not just a correlate.

- Anxious Generation, pg 159.

Let’s look at the quality of these studies. The first study is No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression by Hunt et al. They took 143 undergraduates from University of Pennsylvania and asked them to restrict the time they spent on three apps—Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat—on their phones to 10 minutes a day. They were still allowed to use social media on their computers. The study ran for three weeks, giving students a questionnaire to report how they felt each week.

The study examined seven outcomes (self-acceptance, self-esteem, depression, anxiety, loneliness, fear of missing out, and perceived social support). They found statistically significant results for two of the conditions: loneliness and depression. In other words, for five out of the seven outcomes they examined, there was no statistically significant link between time on social media and the outcome.

So one of the major pieces of evidence Haidt summons in defense of his case is a three week study run on 143 American undergraduates, which are not of the same age as the group he’s concerned about in the first place (which is either 10-14 year olds or 15-19 year olds depending on which graph he feels like using). The students could still use social media on their computers, they could still use all other social media besides Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat, they were incentivized to participate with course credit, and the only way to verify they were staying off of social media on their phones was with screenshots of their battery use screen (see page 757). Finally, as Peter Gray points out, the students knew what the researchers were studying. There are no controls for demand effects (participants are usually motivated to support the hypothesis they think is being studied) or placebo effects (a belief you are doing something that will make you feel better can make you feel better).

The second study Haidt references above is Picture perfect: The direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls by Kleemans et al. They showed 144 girls, ages 14-18 (at least the age range is relevant for Haidt’s thesis this time) instagram-style pictures of other girls, either photoshopped or not. Then they had them rate themselves on a nine-point body satisfaction scale, with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction. The girls shown the manipulated photos scored an average of 4.57; the girls shown the original photos scored 4.94 (page 101, also quoted here3). The difference was statistically significant at the 0.05 level (the p-value was 0.021), but a statistically significant difference is not the same thing as the difference being large. Is the difference large? Prima facie, it doesn’t seem like it. Haidt certainly doesn’t discuss it.

Further, while Haidt applies the conclusions of this study to social media, they could be applied to any setting in which women are seeing curated photos of other women. In other words, the design had nothing to do with the social aspects of instagram, it simply tested how teenagers reacted to images with beauty enhancements. Why not apply the study to TV, magazines, or dance performances? Maybe makeup at large should be banned.

Haidt doesn’t discuss the specifics of these studies, or their drawbacks. Instead, he’s ready to confidently conclude that the “tidal wave” of poor teen mental health is due to social media.

What about the other studies he references in the previous quote? The “dozens of experiments that Jean Twenge, Zach Rausch, and I have collected” that support his thesis? As you might expect by now, these studies are a mess. Both Aaron Brown and Stuart Ritchie have written good criticisms of their quality.

In fact, even researchers in this area have published calls for higher quality studies. In 2021, academic psychologists Candice Odgers and Michaeline Jensen published an overview of research in this area. They write

The most recent and rigorous large-scale preregistered studies report small associations between the amount of daily digital technology usage and adolescents’ well-being that do not offer a way of distinguishing cause from effect and, as estimated, are unlikely to be of clinical or practical significance.

In a 2020 review article on teenagers, screens, and social media, Amy Orben, leader of the Digital Mental Health group at Cambridge, summarizes her results as follows:

When examining the reviews, it becomes evident that the research field is dominated by cross-sectional work that is generally of a low quality standard. While research has highlighted the importance of differentiating between different types of digital technology use many studies do not consider such necessary nuances. These limitations aside, the association between digital technology use, or social media use in particular, and psychological well-being is—on average—negative but very small. Furthermore, the direction of the link between digital technology use and well-being is still unclear: effects have been found to exist in both directions and there has been little work done to rule out potential confounders. (emphasis mine)

In her conclusion she notes that “it is evident that the research field needs to refocus on improving transparency, interpreting effect sizes and changing measurement.” It’s important to note that Odgers, Jensen, and Orben all work in this area. They are incentivized to agree with Haidt—it would bring more public attention and acclaim to their work. The fact that they diverge with Haidt so strongly is a good signal that his thesis is not as watertight as presented.

Despite the poor quality of the studies, there have been meta-analyses attempting to establish whether the literature overall establishes a causal relationship between social media and mental health. The main meta-analysis was done only recently by Christopher Ferguson: Do social media experiments prove a link with mental health: A methodological and meta-analytic review. The study was published in 2025 but available in 2024. He finds that “meta-analytic evidence for causal effects was statistically no different than zero.” (Incidentally, Ferguson was one of the first to debunk the link between violent video games and aggression. What a delicious twist if he does the same for social media.)

Haidt has criticized the Ferguson study (see part I and part II) and I think some of his criticisms are correct. (Others were corrected by Ferguson, and they did not affect the results.) Haidt then proceeds to do his own meta-analysis, and claims that he does find evidence of a causal effect.

But Haidt himself makes several mistakes. Instead of listing them here, I’ll point to Matthew Jané’s interrogation of his methods. Jané is a statistician whose expertise is in meta-analyses. Quoting from his conclusion,

The re-analysis of Ferguson (2024)’s meta-analysis by R\&H [Rauch and Haidt] does not have adequate statistical rigor to build a “case for causality”. Post-hoc subgroup analyses conducted by R\&H did not use a principled statistical model, they did not report any variability in their estimates, the estimates themselves were sub-optimal (unweighted averaging), and they misinterpreted the point-estimates that they calculated. They did not do a proper comparison of their point-estimates and instead they treated them as fixed quantities and simply claimed that these average effect sizes are different without consideration of variability in their estimation procedure.

In sum, I think the verdict on dose-response studies is still out. The existing studies are not of sufficient quality to conclude anything about the effect of social media on mental health, and Haidt is being irresponsible by claiming otherwise.

I.III. Causation part 2: Natural experiments

Dose-response studies are not the only way to study causality.

As I mentioned, dose-response studies assume individual level effects. If Matilda spends more time on social media, then Matilda will be more depressed, regardless of anyone else’s behavior. But social media might manifest itself as a network level effect. If all of Matilda’s friends use social media, she may still be affected by it even after quitting herself. She risks being excluded from social activities and conversations, and might not be able to replace her social media time with in-person interactions.

Haidt says the same on page 160-161:

When [social media] was carried into schools in the early 2010s, on smartphones in students’ pockets, it quickly changed the culture for everyone. Students talked to each other less between classes, at recess, and at lunch, because they began to spend much of that time checking their phones, often getting caught up in microdramas throughout the day. This meant that they made eye contact less frequently, laughed together less, and lost practice making conversation. Social media therefore harmed the social lives even of students who stayed away from it. These group-level effects may be much larger than the individual-level effects, and they are likely to suppress the true size of the individual-level effects.

In fairness to Haidt, I think this is correct. That is, if social media does harm mental health, then I would imagine the effects manifest themselves most strongly at the group level. This could be why we’re seeing such weak results in the individual-level studies we looked at previously.

So how do we study network effects? We want to ask: Is a community better off with less social media? A common way to answer this question is with natural experiments: did people in a community (a high-school, say) become more depressed when social media was rolled out? Ideally we compare two high schools, one which got social media after the other, in order to control for other things happening in the culture at the time. If the school whose students adopted social media become more depressed and the other school didn’t, then this is evidence of causation.

The gold standard natural experiment for this question is the Facebook rollout study by Braghieri et al. The authors took advantage of the fact that Facebook was available at different colleges at different times from 2004-2006. I think this is the strongest study in Haidt’s favor. The authors are careful, the analysis looks well done, and they do find that Facebook had a detrimental effect on the mental health of teens.

Our index of poor mental health, which aggregates all the relevant mental health variables in the NCHA survey, increased by 0.085 standard deviation units as a result of the introduction of Facebook. As a point of comparison, this magnitude is around 22% of the effect of losing one’s job on mental health, as reported in a meta-analysis by Paul and Moser (2009). … The effect of the introduction of Facebook on our index of poor mental health is equivalent to a two-percentage-point increase in the share of students suffering from depression according to the PHQ-9 over a baseline of 25%.

- Braghieri, Levy, Makarin (2022), page 3.

So the best evidence for network-level effects that Haidt could find shows a two-percentage point increase over baseline depression levels. This is not nothing, and hopefully we can get our hands on more studies like this. But combined with the sketchy results of the dose-response studies, is this enough to go-to-green that social media is destroying a generation?

(Stuart Ritchie claims that after adjusting for multiple comparisons — that is, testing multiple things — that the effect disappears. This would be damning for the result if true, but I have been unable to corroborate his findings and he doesn’t cite anything. So I’m going to assume he’s wrong for now.)

Bizarrely, to bolster his point about network effects, Haidt reaches for studies which purport to show that the rollout of the internet had disastrous consequences for the mental health of girls. These studies have problems. But even if they didn’t, this claim doesn’t support Haidt’s argument. Is it the internet at large that’s the problem, or social media? If the former, why is Haidt going on a crusade against social media in particular? If the latter, then why cite studies of the former? Perhaps it’s some secret combination of the two, but we’ll never know because Haidt never tells us.

III. Conclusions

Candace Odgers wrote a review of The Anxious Generation, published in Nature. She accurately summarizes my feelings:

Two things need to be said after reading The Anxious Generation. First, this book is going to sell a lot of copies, because Jonathan Haidt is telling a scary story about children’s development that many parents are primed to believe. Second, the book’s repeated suggestion that digital technologies are rewiring our children’s brains and causing an epidemic of mental illness is not supported by science. Worse, the bold proposal that social media is to blame might distract us from effectively responding to the real causes of the current mental-health crisis in young people.

My goal here is not to prove that social media is net positive, or has no negative effects. I’m open to the possibility that social media has overall adverse effects for some age-groups, and a well-powered, rigorous study could come out tomorrow that would convince me. Some commentators even make some (semi-) compelling cases with arguments distinct from Haidts’ (e.g., Derek Thompson and Richard Hanania, though they also make some mistakes and rely on some bad data).

My goal is instead to argue that the claims in The Anxious Generation are misleading. Even if Haidt turns out to be right, it does not excuse the sloppy way in which the results are presented. Sometimes he draws a fine-grained distinction between social media and the rest of the internet, and sometimes he doesn’t. Sometimes youtube, and dating apps, and blogs, are considered social media, and sometimes they aren’t. He discusses different age groups at different times, and uses studies on college students to justify conclusions about 10 year olds. He reports data and studies inconsistently and selectively, leaving readers with more confidence in his assertions than is warranted. We should demand better of public intellectuals writing books that will reach millions of parents and likely influence public policy around the world.

I’m aware that I’m critiquing this book as a non-parent. I don’t doubt that many parents feel they’re in a bind with social media, sensing that it’s making their teenagers’ lives worse but feeling powerless to do anything about it, lest they damage their relationship with their child. And I don’t doubt that Haidt’s book has an emotional appeal because of this dynamic.

My only advice is to not take Haidt’s conclusions at face value. Even if he is correct, we’re in the world of small, average, effects. Regardless of how many meta-analyses we run, we can never make claims about how any particular child is going to react to social media. You are far more of an expert on your child’s mental health than any social psychologist, simply by virtue of being their parent and spending time with them. And you can talk to them. Solving the problem together is far better than handing down verdicts rubber stamped by ivory tower academics.

Thanks to Sam, Kasra, Rich, and Vaden for feedback.

-

He actually uses 188% instead of 189%. I don’t know why. ↩︎

-

Also, for randomized trials with binary treatments, correlation coefficients are convertible to effect sizes (via Cohen’s d), so the correlation coefficient is relevant for causal questions in this case. ↩︎

-

The first hypothesis predicted that girls would have lower body satisfaction after exposure to manipulated Instagram photos than original photos. This hypothesis was supported, F(1,139) = 4.252; p = .021;r = .17. Girls exposed to the manipulated photos showed to have a significant lower body satisfaction (M = 4.57; SE = .13) compared to girls exposed to the original photos (M = 4.94; SE = .13).

Subscribe to get notified about new essays.