Some thoughts from two-fifths of the way through grad school

August 18, 2024; Updated August 21, 2024

Here are some opinions after the second year of my PhD. I would not consider it any sort of advice. Some of this is geared specifically to PhDs in technical subjects.

It’s not a sprint but it’s not a marathon either. And sometimes it’s a sprint.

Roughly 12 times during your grad school orientation you will hear the line

“it’s a marathon, not a sprint,” implying that you shouldn’t work yourself to death in the short-term and sacrifice your long-term well-being. This misses that creative work has natural peaks and valleys of excitement. At the peaks, it’s healthy (and productive) to be obsessed with an idea and work a lot. This is a sprint. It would be absurd to assume you’ll be equally excited about things all the time. It’s okay to sometimes work more and sometimes work less.

Derek Parfit drank only instant coffee, ate only cold food, and read while on the elliptical so that he had more time for philosophy. The man was sprinting.

It’s easy to write bad papers. I’ve written roughly 15 papers and I’m proud of … four of them. Two of these I wrote in undergrad and two in grad school. I do not recommend this strategy. It does not feel good to write papers you don’t like. And if you don’t like a paper it probably means it’s bad, meaning no one else is going to like it either. The smartest and most knowledgeable grad students I know wrote only a handful of papers in their PhD, but each one was excellent. One insightful paper says much more about your ability to think clearly and creatively than 20 mediocre papers. Pursuing a truly novel idea also teaches you a lot and lays a foundation for future research.

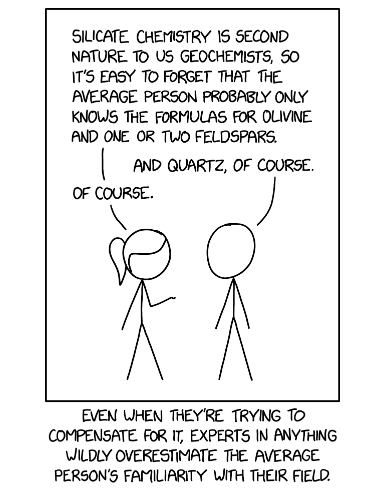

Don’t underestimate the curse of knowledge. Okay, don’t write bad papers. But also don’t underestimate how much you know about a topic. Once you really understand something, you will often think that others will find it obvious. But they won’t. So if the problem was interesting, you should write up your contributions. I think even senior academics sometimes make this mistake, refusing to write a paper they believe is too “simple” even if it could very elegantly solve a worthwhile problem. Simple solutions don’t always equate to bad papers.

Required xkcd comic on the curse of knowledge.

Being overly complicated is the eighth deadly sin. In fact, simple solutions are what you should be aiming for. Or, rather, as simple as possible given the problem. Adding more notation than necessary or writing an overly long and complicated proof when something shorter will suffice is the mark of an amateur. I’ve also noticed that people who spend time trying to make things as simple as possible tend to understand the problem better, which translates to higher quality research.

Popper has a nice quote about the responsibility of scholars to be clear and concise:

Every intellectual has a very special responsibility. He has the privilege and the opportunity of studying. In return, he owes it to his fellow men (or ‘to society’) to represent the results of his study as simply, clearly and modestly as he can. The worst thing that intellectuals can do - the cardinal sin - is to try to set themselves up as great prophets vis-à-vis their fellow men and to impress them with puzzling philosophies. Anyone who cannot speak simply and clearly should say nothing and continue to work until he can do so.

- Karl Popper, from Against big words

Be orthogonal to the hype. If you’re not at the forefront of whatever people are most excited about these days (something-something deep learning), it’s better to be far removed from it. If you’re working on the same thing as everyone else but one-step behind, you’re going to have a bad time. This is a recipe for being the most stressed out student ever. Better to find your own area of interest, ideally several steps removed from the hype. This makes it easier to (1) become an expert, (2) make novel contributions, and (3) be happy since you’re studying something you find interesting for its own sake.

(Yes yes, I’m aware that this is easy for me to say because my research is nowhere close to the hype. But if it’s easy for me to say, maybe I should say it.)

Google scholar sucks. Jon Haidt is convinced that social media is destroying a generation, Greta Thunberg that we’ll be obliterated by climate change, and Eliezer Yudkowski that AI is going to turn us into raw materials. Fine, if we’re going to catastrophize then my nominee for existential-threat-of-the-decade is Google scholar.

Unless you have God-like immunity to the attraction of seeing your citation numbers go up year after year, then Google scholar incentivizes you to study whatever other people find interesting. Tracking your daily citations makes being orthogonal to the hype extremely difficult. Are you going to study some obscure problem that only you are convinced is important? Probably not, because you could get more citations by writing another paper on computer vision. But funneling everyone towards the same research area is a big problem: often the biggest breakthroughs come from obscure areas.

Unfortunately, I’ve been told that Google scholar is basically required when applying for internships. My strategy was to get it and then use a website blocker to keep myself from looking at it. (Flawless system, I know.)

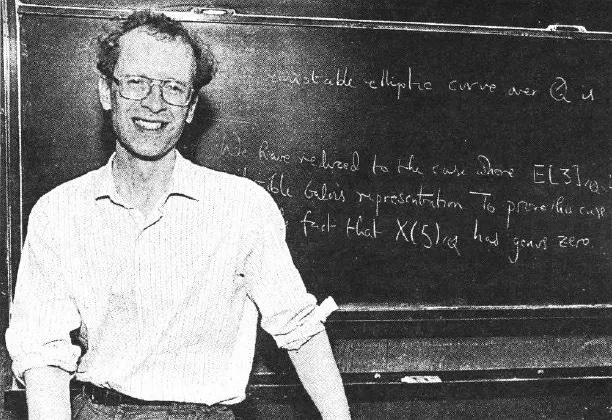

Andrew Wiles didn't publish anything for seven years while he was working on the proof of Fermat's last theorem. His Google scholar would not have been looking so hot.

Not everyone has the same research style. Just like students, professors are good at different things. Some are extremely good at solving technical problems. They’ll write papers with 40 page appendices shaving off logarithmic factors from the best known bounds and they know the Engelbert-Schmidt zero-one law and Fatou’s lemma by heart. If you put a hard problem in front of them, they’ll solve it. Others are good at asking the right questions. They see which way the field is moving and set out to solve a problem which sets the tone of the research to come. They often have a lot of intuition for what the right answer should look like at a high level.

Different skills translate to different research styles. Some like to spend hours at the blackboard with a colleague working through math. Others prefer to work out the details in private, and spend meeting time talking about high-level intuition. Part of your job in grad school is to figure out what kind of researcher you are.

Figure out how to incentivize learning, not papers. When you’re an expert in a field, there’s very little distance between learning something new and producing novel work. If it’s new to you, then it’s probably new to many others as well and it wouldn’t be silly to write a paper about it. This is not true when you’re a junior PhD student. Most things that are new to you are already well-known to the community. But you still need to spend time learning these things because this is how you accumulate enough knowledge to do good research in the future. If you view time spent learning as wasted time (which is remarkably easy to do, especially if all your friends are writing NeurIPS papers) then you’ll end up focusing on easier but less worthwhile projects.

How to incentivize this will depend on you. I blog and write notes. You could also aim to be the go-to person in your cohort about a certain set of subjects, or to be the most insightful person during seminars.

Computer science departments are not weird enough. I have a theory: A PhD in machine learning is the new MBA. You can expect to earn a lot of money afterwards, and many people are there for connections and job opportunities. It used to be (and still is in many departments) that pursuing a PhD was not financially rewarding or helpful for your career. Computer science departments now have much closer relationships with industry, which changes their research incentives away from tentative, longterm, high-risk research and towards very concrete and tangible research.

Who could be against tangible and concrete progress? Me. I think academia should be the home of foundational research that may or may not pay off in the long run. If not academia, where else? Private industry has a hard time incentivizing basic science because it tends to take several decades to turn new science into usable products. Once we know something works and it’s a matter of scaling it up, then industry can pick up the idea and run with it. They have more money and more incentive to turn things into usable products.

The professionalization of the field also has consequences for the kinds of people pursuing PhDs. As Dave Masters told Stoner, academia should be the home of weird nerds—quirky people with weird work habits obsessed with niche questions—but computer science departments (or, at least, the ML portion of computer science departments), are less and less hospital to weirdness. (In fact, this is maybe the case in academia more generally, see Alexandra Tuslo on the flight of the weird nerd from academia.)

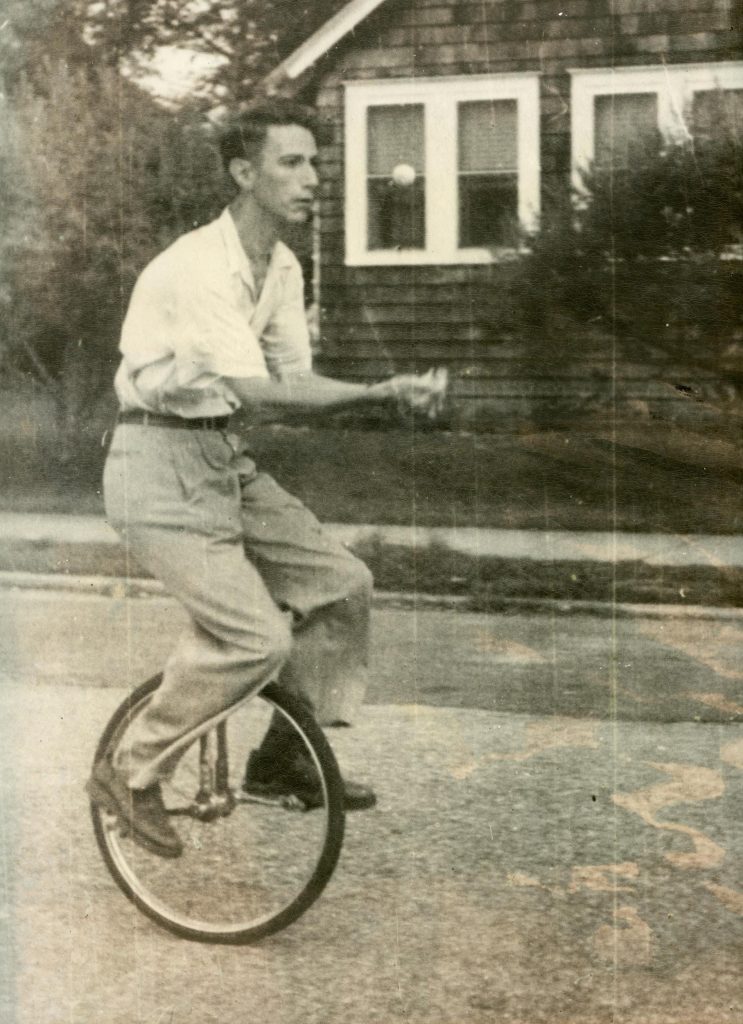

Here, then, was a picture of Claude Shannon, circa 1955: a man—slender, agile, handsome, abstracted—who rarely showed up on time for work; who often played chess or fiddled with amusing machines all day; who frequently went down the halls juggling or pogoing; and who didn’t seem to care, really, what anyone thought of him or of his pursuits. He did what was interesting.

A description of Claude Shannon from The Idea Factory. I don’t think Shannon would be welcomed in a computer science department today.

You can separate yourself with speaking and writing skills. If you’re doing a PhD in maths, statistics, computer science, physics, etc., odds are that you’re already in the top percentile for analytical skill. This means that in absolute terms, you are not that much better or worse than your neighbor at solving a complicated homework problem. This is not the case for speaking and writing skills. PhD programs rarely select for these abilities, so the variance among people is huge. This is especially true for speaking skills (most academics learn to write well eventually). If you’re a demonstrably good speaker and writer during your PhD, it will open doors.

Take yourself seriously as a scholar. Benefits to your self-esteem aside, this is your debt owed to society. You have been gifted a position where you get paid to learn things. This is a privilege. The least you can do is take your ideas seriously, learn to explain your research to lay audiences, and try to solve interesting and important problems. (None of this involves being an unpleasant or overly serious person.)

People who took time off are happier, on average. This is obviously hard to say conclusively, so I’ll just say it inconclusively and hazard some guesses as to why it might be true.

For one, if you’ve taken time off between grad school and undergrad, then you’re usually coming back for a good reason. And that good reason will help sustain you even when your research is not going so well. Second, you are more fleshed out as a person. Your identity in undergrad is basically student, so if you go to grad school immediately you haven’t had that much time to form non-academic pillars for your life. This makes it hard if you hit rough patches in your PhD, because it can feel like your entire life is crumbling. But if you have a well-established identity outside of academia, then it’s easier to handle the natural ebbs and flows of grad school.

Ulrich Horstmann, an advocate of philosophical pessimism, thinks we should purposefully use nuclear weapons to wipe out humanity because "the true Garden of Eden is desolation." I'm willing to bet he was not the happiest grad student. From what I can gather from his German CV, he didn't seem to take time off before grad school. Case closed?

Your advisor matters. Another cliche is that your advisor makes or breaks your PhD. This one is, unfortunately, true. I say unfortunately because you have limited knowledge when choosing your advisor. It’s difficult to learn what people are like to work with before actually working with them. You can talk to their students (and you should), but this is still imperfect information since students also have their own quirks and personalities. So landing on a good advisor is partly luck.

Vibes matter. Maybe this is motivated reasoning because I live in Pittsburgh, but I think your day-to-day happiness in a PhD is determined much more by your department than your city. If you live in New York but dislike your cohort, your advisor, and your research, then no matter how many visits to the comedy cellar you can cram in on the weekends, you’re going to be miserable. But if you like your program and have good friends, it’s easy to put up with a mediocre city.

You should think really hard before going to grad school. The most serious, the most obvious, and also the most important point. Grad school sucks for a lot of people. The mental health statistics are abysmal. Depression skyrockets and suicide is many times as prevalent as it is among the normal population. Even though the difficulties of grad school are somewhat common knowledge, people still treat it like a default option. Grad school is the worst default option imaginable. Notwithstanding the comments about it being the new MBA above, the hours are long, the pay is low, and unless you’re extremely curious about what you’re studying then you’re going to be miserable. Most grad students are in their twenties. You should not be spending these years anxious and depressed.

Thanks to Vaden for pointing me towards the Popper quote.

Back to all writing

Subscribe to get notified about new essays.