The statistics wars via Royall's three questions

February 12, 2025

- Royall’s three questions

- Question 1: What should I believe?

- Question 2: What should I do?

- Question 3: How much evidence does this provide?

- What happens in practice?

Royall’s three questions

In Statistical evidence: A likelihood paradigm, Richard Royall asks three questions that various schools of thought in the foundations of statistics have tried to answer in the past century:

- What should I believe?

- What should I do?

- How much evidence does this observation provide for a hypothesis?

Royall focuses on the third question, arguing that any reasonable answer must rely on the “likelihood ratio” (a view called the law of the likelihood).

But Royall’s questions also serve as a useful frame on the debates at the foundations of statistics. They highlight the distinctions between various schools—Bayesian and frequentism, pragmatism versus puritanism, and disagreements over what the role of statistics really is and how probability should be used. Here I’ll try to show that much of the debate arises because various schools of statistical thought are trying to answer different questions.

A reader could be forgiven for staring in bewilderment at the phrase “debates at the foundations of statistics.” Are there such things? What is there to debate about tallying the number of car crashes in Missouri, or calculating the standard deviation in the heights of school children? Regrettably, this is a reasonable question because of the way statistics is taught … everywhere. The stale view of statistics taught from grade school to undergraduate haunts every grad student who, at the bar, is asked “what do you do?”

In fact, statistics has been the epicenter of more feuds and controversies than most fields. Throughout the 20th century, entire academic departments would often pick a side and staunchly refuse to hire anyone with the opposing perspective. Deborah Mayo calls these the statistics wars. Statisticians believed the very foundations of reason itself were at stake. Ronald Fisher, one of the more colorful characters in the discipline’s history, is said to have called one of his colleague’s views “horrifying [for] intellectual freedom in the west.”

Here I’ll give a brief tour of how I think about the statistics wars. I’ll try to be mostly impartial—I’ll explore where I personally sit in future posts.

A note before we begin: Statistics is written in the language of probability, and debates about one usually bleed into debates about the other. Views on the proper use of statistics often directly follow from your views on the nature of probability, and vice versa. Here I’ll touch on both the philosophy of probability and the philosophy of statistics, separating them only if appropriate.

Question 1: What should I believe?

The idea that probability can and should be used to model beliefs is held most firmly by the Bayesians, a school of thought named after the 18th century reverend Thomas Bayes1. This is not to say that other schools think that statistics has no role to play in shaping our beliefs (it’s supposed to help us reason about the world, after all), but the Bayesians are unique in how formally they make the connection between probability and belief.

In the Bayesian conception, everything should be treated as a random quantity and everything is thus amenable to probabilistic analysis. Whereas most people would consider “the number of people who sneezed on December 21st, 1988, in Accra, Ghana” to be a fixed (deterministic) but unknown number, Bayesians treat this as a random variable drawn from some distribution. They begin with a guess for what this distribution is (a prior distribution), and then slowly change their guess as new information arrives (a friend reports they saw 12 people sneezing). The process of changing the distribution over time is known as Bayesian updating.

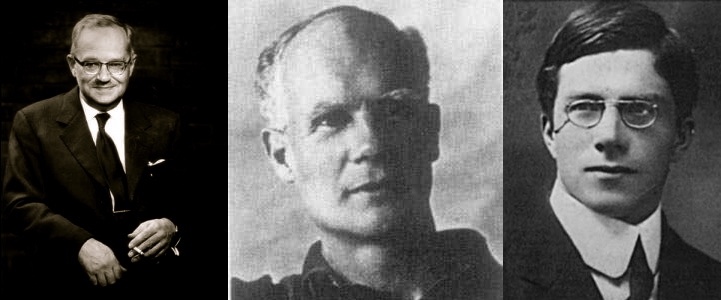

Pierre Simon de Laplace (right) was the main reason that Thomas Bayes' (left) ideas caught on, and why they were originally tied to rationality.

While one can use Bayesian methods for purely pragmatic reasons, if you push Bayesian practitioners hard enough they will typically justify the use of their methods by appealing to the Bayesian interpretation of probability, which claims that degrees of belief are represented by probabilities. This is the core claim behind the Bayesian philosophy and is the link between Bayesianism and Royall’s first question. Bayesians contend that belief is best handled using the tools of probability theory and that the role of statistics is to formally update these beliefs using data.

For Bayesians, this link between rationality and probability is more than mere analogy. They have developed frameworks to formally connect the two. The most famous of these is Cox’s theorem which posits that the beliefs of a rational agent must be treated as probabilities and obey certain arithmetical axioms. Cox was reacting to Kolmogorov’s axioms, which are the most widely used axioms of probability theory but have nothing to do with rationality or belief. Unfortunately for Cox, while his axioms are the subject of the occasional philosophy seminar, they are never used by practicing statisticians (not least because they do not handle countable additivity, a technical yet crucial property when dealing with all but the simplest sample spaces).

Most modern Bayesians appeal instead to Dutch book arguments to justify the connection between probability and belief. These say that if you assign numerical values to your beliefs and bet on them, then you are guaranteed to lose money unless your beliefs are consistent. That is, you should not bet at 3:2 odds that a coin will come up both heads and tails, otherwise a bookie can take both bets and be guaranteed to make money from you. Dutch book arguments are cleaner than Cox’s theorems, but significantly less powerful. They show only that if you are willing to assign numbers to your beliefs and want to bet on all outcomes, then your beliefs should be consistent. They don’t tell you why you should assign numbers to your beliefs in the first place, nor how to update your beliefs in the face of new evidence, a core part of Bayesianism.

A technical but important caveat: Because Bayesianism has entered the mainstream due of movements like effective altruism and Βay-area rationalism, there is naturally tremendous confusion over what exactly it means. This is not helped by people with names like Nate Gold and Liam Silver who write books confusing using Bayes’ theorem with Bayesianism itself. Everyone uses Bayes’ theorem, it’s simply a mathematical identity. The identifying feature of Bayesianism is treating unknown parameters as random quantities. Bayesians put distributions over things that other statisticians would rather die than treat as random.

Objective vs Subjective Bayesians

There are a couple of sub-schools of Bayesian thought, the main ones being subjective and objective Bayesianism. The split comes from a disagreement over how one should assign prior probabilities. Before you see any data, what should the distribution be over the number of people who sneezed in Accra, Ghana? Perhaps it should be uniform over the population, or perhaps it should be a Gaussian centered at 10?

Objective Bayesians (sometimes called logical Bayesians) are of the view that there is a single, correct prior that should be used. They typically appeal to symmetries and rational constraints to determine what it is. For instance, they would typically take the view that the correct prior to have when estimating the bias of a coin is 50/50 heads/tails because there is no reason to favor heads over tails and vice versa.

The father of objective Bayesianism is arguably Harold Jeffreys, though Keynes introduced many of the concepts first. But Keynes didn’t think that all beliefs were quantifiable, setting him apart from most Bayesians. Jeffreys introduced the Jeffreys’ prior which is often appealed to by objective Bayesians as the correct prior. Other notable objective Bayesians are Rudolf Carnap, ET Jaynes, and James Berger.

The hulking figure of Frank Ramsey, who made seminal contributions to combinatorics (Ramsey numbers and graphs), optimal taxation (Ramsey rule), expeced utility theory (helped formalize it), and laid the foundations for modern subjective Bayesian theory.

Subjective Bayesians, as you can probably guess, disagree that there is an objectively correct prior. They think of probability as something much more personal. Everyone will have a different prior to reflect their own thinking and assumptions. In the modern era, the two figures most associated with the subjectivist school are Frank Ramsey (see his 1926 paper truth and probability) and Bruno de Finetti (if you speak French, see his 1937 paper La prévision: ses lois logiques, ses sources subjectives). Other key figures in this tradition are LJ Savage and JL Doob.

Question 2: What should I do?

Battles in the history of statistics are often framed in terms of Bayesianism versus frequentism. Frequentist methods treat unknown parameters as fixed (the number of people who sneezed in Accra, Ghana isn’t random, it’s deterministic but unknown), and then perform inference on them. In other words, for the frequentist the only randomness comes from the data.

In terms of outcomes that practicing statisticians actually care about, frequentism has mostly won the day. Confidence intervals, minimax rates, type-I and type-II error guarantees are all frequentist notions of performance.2 And even when statisticians use Bayesian methods, they usually try to measure performance of those methods with frequentist notions (see, e.g., the Bernstein von-Mises theorem).

But just like Bayesianism, there are divides within frequentism as well. The most famous of these is the battle between Jerzy Neyman, Egon Pearson, and Ronald Fisher, which began in the 1920s and lasts until this day. The disagreement is usually framed in terms of hypothesis testing, but it’s really over what statistics is trying to do as a discipline. The Neyman-Pearson camp were focused on Royall’s second question, while the Fisherian camp was focused on the third.

Neyman and Pearson considered statistics to be about action; about what to do next. For Neyman in particular, statistics is a branch of decision-theory. He called mathematical statistics the search for “inductive rules for action”, meaning we’re making decisions informed by the data we’ve gathered.

The problem of testing a statistical hypothesis occurs when circumstances force us to make a choice between two courses of action: either take step A or take step B…

- Neyman, A first course in probability and statistics, 1950, pg 258.

The influence of the Neyman-Pearson approach to statistics can be felt every time universities offer classes on “decision-making under uncertainty,” which invariably use statistical decision theory to make “data-driven decisions”. In hypothesis testing in particular, we often test the null hypothesis against an alternative hypothesis, choosing to accept one and reject the other. This also comes from Neyman and Pearson, who thought it was nonsensical to simply test a single hypothesis (as opposed to Fisher, as we’ll see when studying the third question.) For them, one can only evaluate the relative merits of two hypotheses; you can’t say anything sensible about one hypothesis on its own.

You might think that the Neyman-Pearson paradigm, and Royall’s second question more generally, are still about belief. After all, won’t you only choose action A instead of action B if you believe A and not B? Isn’t talking about decision making just a sneaky way to talk about belief? Νο, for several reasons:

- You might believe neither A nor B is true (replace true with closest to true if you’re an adamant fallibilist). Suppose you’re a doctor and a patient presents with symptoms of Malaria. Even though you’re quite sure it’s Malaria, you might order a test for yellow fever as well. If it turns out, based on the data, they’re more likely than not to have yellow fever, you might order extra screenings despite maintaining a belief that they really have malaria.

- Utility versus belief. You work in public policy and are deciding whether to roll out a new congestion tax. The economists in your department have run a small study: implementing the tax reduces the average number of cars on the road by 10%, but also disproportionately affect the poor. While you might now believe that congestion taxes are effective, they are not effective enough to warrant implementation.

- Lack of alternatives. Now you’re a physicist. You predict a new particle, particle X, based on the standard model of particle physics. We run some tests to look for particle X, but we don’t have sufficient evidence to reject the hypothesis that the particle doesn’t exist (the null hypothesis). Do you stop believing in the existence of the particle? Maybe, but maybe not. The standard model is our best theory. Until a coherent, alternative theory is proposed that does not have a particle X, it may not be sensible to entirely discard the idea of a new particle.

Neyman himself was adamant about the distinction between Royall’s first and second questions. He made sure to highlight the difference between action and belief:

The terms ‘accepting’ and ‘rejecting’ a statistical hypothesis are very convenient and are well established. It is important, however, to keep their exact meaning in mind and to discard various additional implications which may be suggested by intuition. Thus, to accept a hypothesis H means only to decide to take action A rather than action B. This does not mean that we necessarily believe that the hypothesis H is true. Also if the application… ‘rejects’ H, this means only that the rule prescribes action B and does not imply that we believe that H is false.

- Neyman, A first course in probability and statistics, 1950, p. 259.

Question 3: How much evidence does this provide?

Ronald Fisher—often called the father of modern statistics, seeing as he invented half the methods covered in a first year grad course—thought that statistics was in the business of quantifying evidence. This is a very natural idea and is in fact how statistics is often taught. If we have the hypothesis “smoking cigarettes causes lung cancer,” we collect data from smokers and non-smokers, see how many of each have lung cancer, and check to what extent the results refute our hypothesis.

Fisher developed the p-value—bane of students and social scientists alike—for precisely this purpose. The p-value is a number that is computed from a dataset. The smaller the p-value, the more inconsistent the data is with a given hypothesis. Legend has it that Fisher developed the p-value trying to test if his colleague Muriel could tell if milk was placed in tea before or after the hot water. (She could … probably.)

Neyman (left), Pearson (center), Fisher (right). The progenitors of the statistics wars.

Because Neyman and Pearson were focused on action, they always thought statistical testing should involve a null and an alternative hypothesis. Accepting a hypothesis meant choosing one action over another. Fisher, on the other hand, thought it was perfectly sensible—and preferable—to examine a single hypothesis and try to quantify the evidence in its favor.

Fisher was concerned that the Neyman-Pearson paradigm confuses policy and science. He thought that statisticians should be in the business of helping people tell to what extent the data disqualifies a particular hypothesis. What to do with that information is up to others. For him, the statistician is not the decision-maker, he’s the lab tech.

Fisher, Neyman, and Pearson went back and forth, attacking each other in writing and trying to ensure that the statistics community adopted their preferred position. Fisher compared Neyman to

Russians [who] are made familiar with the ideal that research in pure science can and should be geared to technological performance, in the comprehensive organized effort of a five-year plan for the nation.

- Fisher, 1955, pg 70.

He goes on to suggest that Neyman and Pearson are sacrificing truth for economic value:

In the U.S. also the great importance of organized technology has I think made it easy to confuse the process appropriate for drawing correct conclusions, with those aimed rather at, let us say, speeding production, or saving money. There is therefore something to be gained by at least being able to think of our scientific problems in a language distinct from that of technological efficiency.

What happens in practice?

In terms of how scientists and social scientists use statistics in practice, very few are concerned with Royall’s first question. Seldom, if ever, do papers give explicit probabilities for the authors’ beliefs, nor claim a right to tell the reader what to believe. Using statistics to mathematize beliefs has mostly left industry and academia, insteading ending up in niche (or perhaps not so niche) corners of the internet.

However, statistical practice today—especially hypothesis testing—is an awkward blend of both the second and the third question. In Mindless Statistics, Gert Gigerenzer calls attention to the “null ritual”, which is the standardized hypothesis testing procedure taught in many textbooks and graduate programs to psychologists and social scientists.

The null ritual:

- Set up a statistical null hypothesis of “no mean difference” or “zero correlation.” Don’t specify the predictions of your research hypothesis or of any alternative substantive hypotheses.

- Use 0.05 as a convention for rejecting the null. If significant, accept your research hypothesis. Report the result as p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001.

- Always perform this procedure.

There’s no alternative hypothesis specified in the null ritual, which makes it Fisherian. But we’re also making a binary decision about whether to accept or reject the null, which is firmly in the Neyman-Pearson camp. However, we also report the p-value, which is again Fisherian.

This may not seem like an issue—so what if we’re combining two perspectives? But it leads to trouble.

For one, we’re including irrelevant information. In the Neyman-Pearson paradigm, the p-value has no use beyond comparing it to the pre-chosen significance level (0.05 in the null ritual). If the p-value is less than 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis. If not, we don’t. This means that a p-value of 0.049 and 0.00001 have the exact same implication for decision-making. So what are we doing by reporting it?

Unfortunately, this extra information is not only irrelevant, it’s actively harmful. Reporting the p-value alongside the decision (accept/reject) confuses the p-value for the significance level, resulting in invalid statistical guarantees. You can read more about the issues here, but the non-technical overview is that the null ritual makes it dangerously easy to make false and misleading claims.

The upshot is that the statistics wars haven’t been fought and won, they’re still being fought.

Thanks to Rich for comments.

-

While Bayesianism is usually laid at the feet of Thomas Bayes, it can arguably be traced back to Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat in a correspondence between 1654 and 1660 about what rational gamblers would do in games of chance. (These letters are often associated with the birth of probability itself). Also, while Bayes’ discovered (a simple version of) the theorem that Bayesians use to update their beliefs, it’s unclear that he would have endorsed Bayesianism as practiced today. Pierre de Laplace actually did much more to popularize Bayes’ contributions than did Bayes himself, and also made the formal connection between belief and Bayes’ theorem. Laplace took an equation that was published post-humously by Bayes in 1763, and drew the connection to human belief. In fact, the original paper by Bayes and Price does not contain the words “belief”, “credence”, “rational”, etc. But Laplace, the stalwart academic, duly credited his insights to Bayes, and the philosophical school which links belief and probability is known as “Bayesianism”. After Laplace, however, Bayesianism mostly lay dormant until the 20th century, when it was revived by figures such as Ramsey, Finetti, and Jeffreys. ↩︎

-

They are all claims about what properties your method has if you run it many times. Eg, a 95% confidence interval says that if you run the experiment n times, then the true parameter will be in your confidence set 95% of the time as n tends to infinity. ↩︎

Subscribe to get notified about new essays.