On studying useless things

August 01, 2024

We have concluded that the trivial mathematics is, on the whole, useful, and that the real mathematics, on the whole, is not.

- G.H. Hardy

How do you justify a life spent studying a subject with no immediate practical applications? There are many problems in the world, from death, disease, and depression, to political oppression and social turmoil. Can one stare such suffering in the face and then turn around and study pure mathematics, theoretical physics, or the chemical bonds of obscure elements?

I think about this question a lot. After several failures to do “practical things” I ended up pursuing a PhD in theoretical statistics which, for anyone who is not a statistician or mathematician, looks indistinguishable from pure maths. This can make for awkward dinnertime conversations. After your cousin explains how she rescues dogs or your uncle discusses his latest ICU patient, explaining that you’ve developed a new proof technique for the concentration of Lipschitz functions falls remarkably flat.

Some theoreticians take pride in being “useless,” thinking of what they do as having its own intrinsic benefit, akin to producing a novel or a poem for other artists to enjoy. G.H. Hardy, a famous Oxbridge mathematician, advocated this view, taking pride in the fact that number theory—the “queen of mathematics”—had no applications.

G.H. Hardy.

I don’t feel this way. I wish my interests and aptitudes aligned with one of the many problems I’d love to see solved—getting humanity to Mars; reducing rates of depression; increasing and extending quality of life; pandemic preparedness; eradicating various diseases; creating viable artificial wombs; increasing access to knowledge; reducing class disparities; and so on.

But the fact is the day-to-day work of an entrepreneur or software engineer or founder simply doesn’t appeal to me as much as proving theorems does. So it’s worth asking: Is this purely an exercise in self-aggrandizement, or does fundamental research in mathematics and the basic sciences have any benefit?

I believe the answer is yes, but the benefits are delayed, unpredictable, and uneven. Fortunately for my ability to sleep at night, however, I’m also convinced that we can’t do without it.

Let’s first discuss fundamental research more broadly, which includes not only mathematics and statistics but also foundational biology, chemistry, and physics. Such research has downstream benefits in terms of new technology, but the benefits take time to materialize. Perhaps a neurobiology lab discovers a new function of the hippocampus, which in turn suggests a new intervention for some rare disease. But this process can take years, because (i) discovering new things is hard and error-prone, (ii) it’s not always obvious how to leverage new discoveries, and (iii) moving from a proof of concept to a product that’s mass marketable requires funding, regulatory approval, and good engineering.

We can try and study the returns to basic science quantitatively. Skeptical as I am of many economic models, it’s a robust finding that research in maths and science has positive returns to economic growth. The mechanism is no mystery: you can imagine scientific advances as replenishing a reservoir of knowledge that can be mined to create new technologies. Scientific American (unbiased, I’m sure) claims that between a third and a half of economic growth in the US resulted from basic research. This paper has a giant table summarizing the literature on the relationship between economic growth and basic research, measured by publications. Most find a positive relationship (and sometimes causality) between the latter and the former.

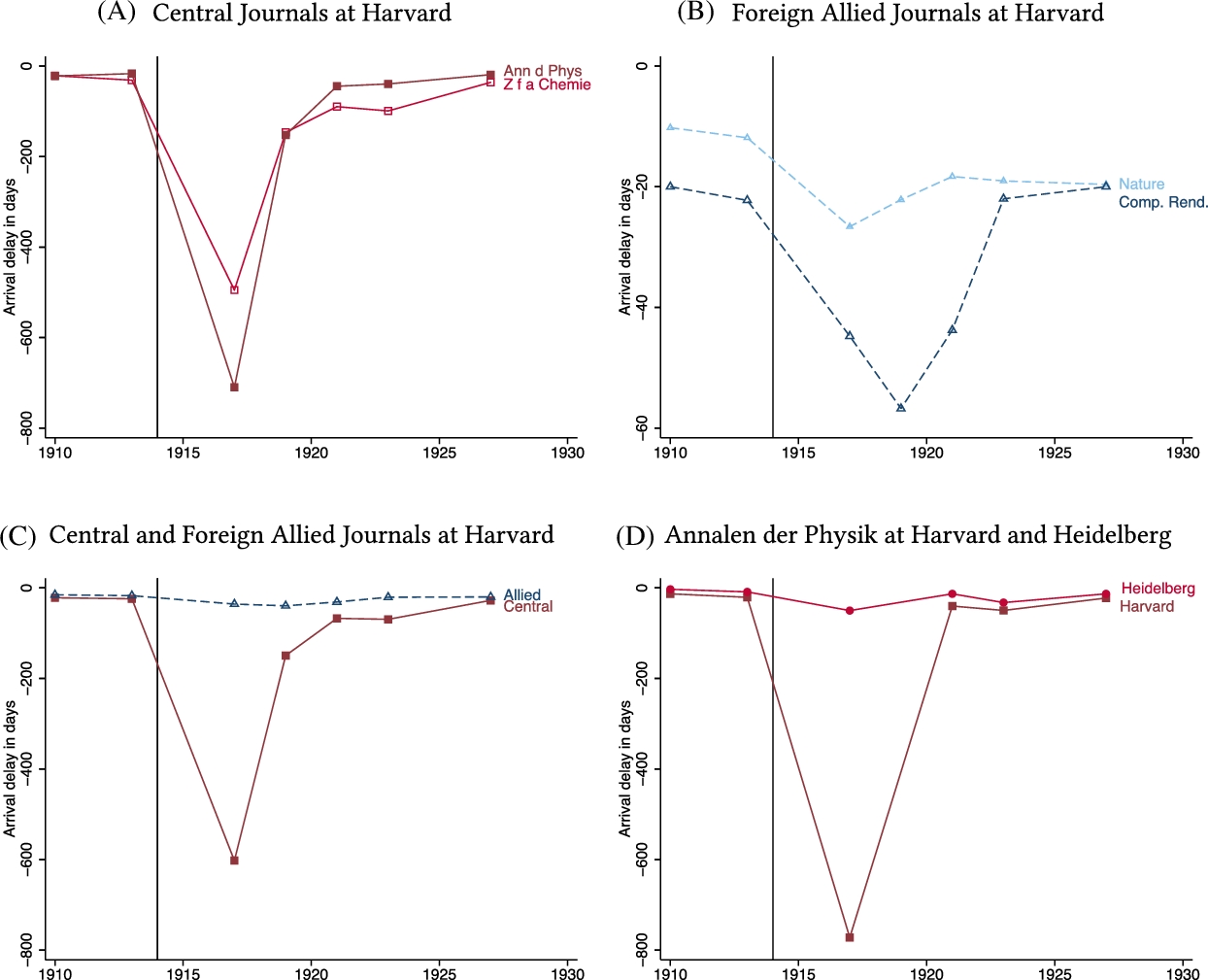

You can also study natural shocks that disrupt or increase funding (such as wars) for basic science and see what happens. Matt Clancy has an excellent summary of such research and finds that more science means more innovation and more technology. He also finds that it takes roughly 20 years on average to go from an increase in basic science research to obtaining the corresponding economic gains.

Iaria, Schwarz, and Waldinger (2018) use the fact that scientific communication was disrupted between the axis and allied powers during WWII to study effect of fewer novel ideas on progress. Matt clancy reviews this paper here.

Of course, these results concern science as a whole. This says nothing about what any particular scientist is working on. Some advances will make their way into new technology in the coming decades, some will wait their turn on the bench, and some will never even get dressed for the game. Unfortunately, there’s no way to tell which are which beforehand.

By pursuing fundamental research, you are part of a collective of people all pushing the frontiers of our knowledge into the unknown. Many—perhaps most—of these efforts won’t pay off in terms of practical benefits, but the project as a whole is still worth it for those that do. We’re exploring this great frontier together, not sure which discoveries will lead where, but confident that some can change our lives for the better.

That science results in economic growth and innovation might be easy to imagine in the case of biology, chemistry, and physics, where intimidating people in white lab coats run experiments which can lead to improvements in medicine, manufacturing, and electronics. But is this argument true of mathematicians and statisticians? Of theorists who spend their days scribbling on paper and then throwing out 99 out of every 100 sheafs?

Some math is clearly useful. Engines, bombs, smartphones, airplanes—anything with a microprocessor was designed by an engineer who used math at some point in the process. Whether the boolean logic used to derive the circuit, or the geometry of the wings of an airplane, if you removed math from the process nothing would get off the ground.

But all of these applications use math that is very old and not very sophisticated. What about more abstract, theoretical mathematics?

This objection is best answered by simply listing examples. Hardy’s favorite useless subject, number theory (and elliptic curves in particular), turned out to be central to cryptography; the Radon transform is integral to tomography; differential geometry describes the curvature of spacetime and is core to general relativity; topology is used to unfold large telescopes in space, conic sections (studied as pure maths by the Greeks) turned out to describe planetary orbits in Newtonian mechanics; spectral theory turned out to describe actual physical spectra (one of the great nominative coincidences of all time); measure theory turned out to be central to probability theory, which is in turn central to many areas such as quantum mechanics and neural networks; concentration inequalities turned out to be central in clinical trials and A/B tests. Gottfried Liebniz seems to have invented calculus without any application in mind.

Still, this doesn’t answer the question of whether such math needs to be developed before its applications, or whether it could have been invented only when needed. In fact, many branches of mathematics were initially pursued because of some practical problem. My field of study, sequential analysis, was invented during World War II because Milton Friedman and W. Allen Wallis wanted to reduce the number of samples required to determine the efficacy of anti-aircraft fire on dive bombers. Joseph Fourier introduced the Fourier series in order to solve the problem of how heat propagates in metal bodies. The physicist Edward Witten invented so much new mathematics to develop string theory that they gave him the fields medal. Isaac Newton, who simultaneously but independently invented calculus alongside Liebniz, did so motivated by problems in physics.

Abraham Wald worked at the Statistical Research Group from 1942-1945 at Columbia university and nearly single-handedly invented sequential analysis.

Practical problems that pose mathematical questions encourage mathematicians to work on them. So can’t we just solve problems as they arise? What’s the point of trying to do math for math’s sake? Two reasons.

For one, we’ll solve problems faster if the relevant math is already understood. Wallis and Friedman asked the initial question that sparked interest in sequential analysis in 1942. Out of their mathematical depth, they handed the problem over to Abraham Wald. But it took Wald several years to flesh out the ideas—publications on even relatively simple problems did not start appearing until 1945. Had sequential analysis been developed earlier, its insights could have contributed to the war effort much sooner.

Second, math developed for particular applications typically has a very specific flavor. Almost by definition, it’s not as general as it could be because generality is not the goal. But it is only when mathematics is formulated as generally as possible that the connections between different areas are fully realized, and it’s precisely such connections which lead to the deepest insights. And generalization falls into the realm of pure mathematics since you are leaving the specifics of the application behind.

Generalization is responsible for the relationship between geometry and algebra, which you’ve seen in its simplest form if you’ve ever plotted an equation on a graph. Engineers are relying on this connection whenever they find solutions to systems of polynomial equations, and it’s used in control theory, robotics, coding theory, and genetics. Generalization is also responsible for category theory, which has found applications in programming language theory, quantum field theory and natural language processing. In the words of a stack overflow user responding to requests for applications of category theory: “The question is too broad. Category theory plays roles in half of mathematics.”

In my own field, generalization was responsible for a unifying perspective on concentration inequalities which led to tools that are now used by many tech companies.1 The work of mathematicians on merging geometry and calculus and generalizing the technique to higher dimensions gave Einstein the relevant tools for general relativity, without which your GPS wouldn’t work. Claude Shannon leveraged boolean algebra, then an abstract mathematical topic and a generalization of Liebniz’s algebra of concepts, to show how circuits could be designed to perform logical operations. Every personal computer to this day is built using boolean algebra. The list goes on and on.

Theoretical research might be conceived of as pushing our knowledge in various areas as far as possible, to see if and where it meets our knowledge in other areas, and to forge connections with other problems. It’s hard to justify these explorations before these connections are found, but we’re glad to have done it when they are. And the more we know, the more connections we can make.

Can we prove beyond a doubt that pursuing fundamental research is integral to progress? No, but it would be foolish to ignore its role in economic growth and in helping us solve more applied problems. Given that we know it can and has helped move us forward, studying useless things is not so useless.

Back to all writing

Subscribe to get notified about new essays.