An epistemological Frankenstein

September 22, 2023; Updated November 25, 2023

Superforecasters predict the future. Or try to, at least.

The “science” of superforecasting emerged from Philip Tetlock’s work in the 1990s. He demonstrated that most political pundits were extremely bad at predicting the future—often no better than chance. But a small group of people were consistently better than average, and Tetlock dubbed these enlightened souls superforecasters. Since then, a variety of organizations have been founded to promote and study superforecasting. Chief among them are the The Good Judgment Project (GJP), founded by Tetlock himself, and the Forecasting Research Institute (FRI).

If you’re like me—if you’re like most people in fact—this sounds … suspicious, to say the least. I think this skepticism is warranted, and we’ll get to some reasons why soon. But there are also some people who believe in the power of superforecasting, as evidenced by the organizations above. Culturally, the people who seem the most excited about superforecasting are often rationalists (of the Bay area variety), and/or effective altruists. Forecasting is a dominant theme on LessWrong, ACX, and the EA forum, and all the various discords and discussion groups associated with these groups (all those of which I’ve been a part, at least).

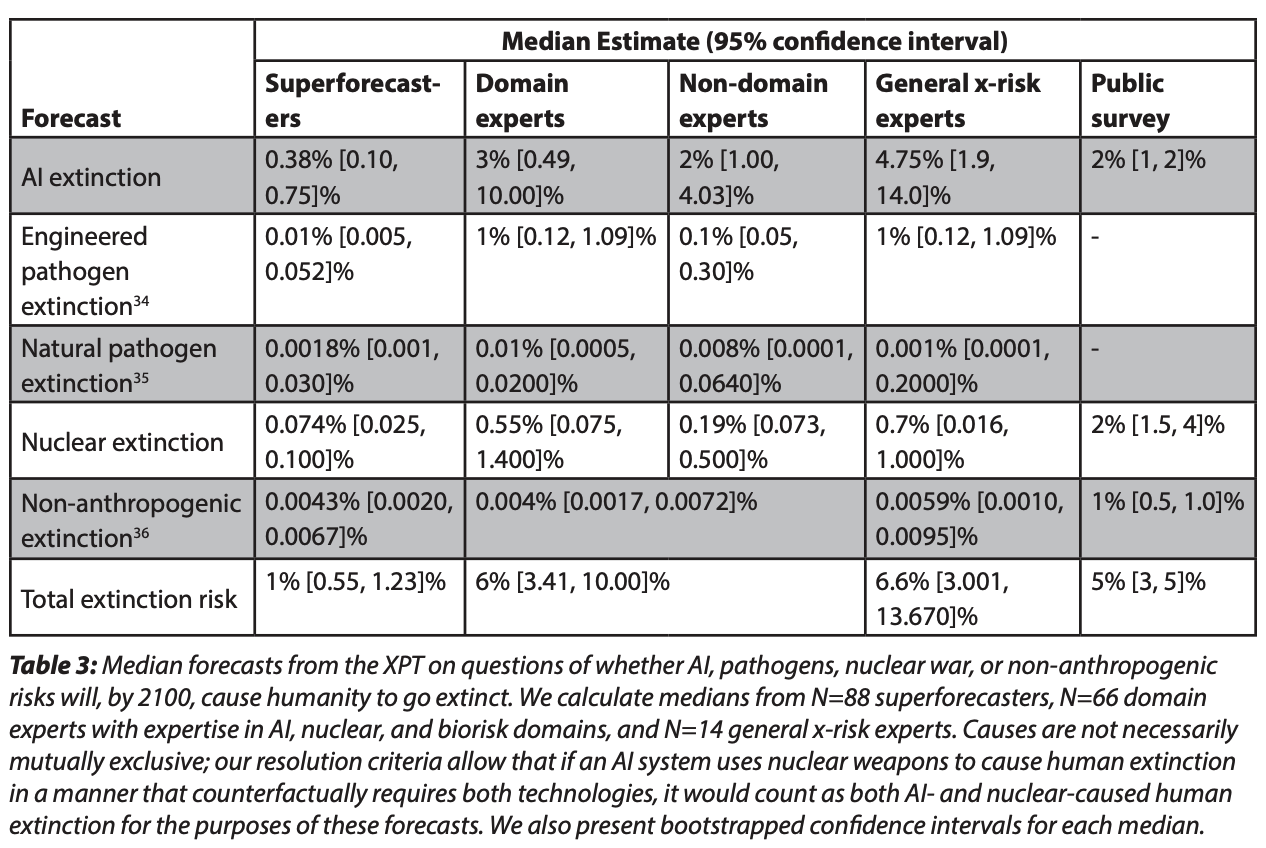

Recently, the FRI held a tournament where superforecasters were asked to predict the likelihood of various existential risks. Quoting from the website: “We asked tournament participants to predict the likelihood of global risks related to nuclear weapon use, biorisks, and AI, along with dozens of other related, shorter-run forecasts.” Here are some of the results (you can see all results here):

These are the cumulative results of a bunch of superforecasters (88 to be precise) predicting whether humanity will go extinct from various threats. There are a couple of intriguing results.

For one, superforecasters are a relatively optimistic lot compared to their historical counterparts. Traditionally, those who claim to be peering into the future, however dimly, are prophets of death, ruin, and destruction. Think of your Vogts, Ehrlichs, Malthus’, Ivanhoes, and Hubberts. It’s refreshing that, in this study at least, superforecasters are courting the more hopeful side of future.

Second, there is a big gap between the superforecaster estimates regarding AI and those of the rationalists. Superforecasters assign only a 0.38% chance of extinction by AI, while the rationalist estimates tend to be much higher. In The Precipice, for instance, Toby Ord estimates a one-in-six chance. Yudkowsky seems to think it’s basically 100%. Scott Alexander thinks it’s around 33%. Max Tegmark says 50%. Paul Cristiano says 22%. (Of course, all of these estimates fluctuate a lot because Bayesianism doesn’t really make any sense in this context, but you get the point.)

These discrepancies give us an opportunity to check how seriously rationalists take superforecasting. Remember: superforecasters are supposed to be far better than any of us at predicting the future. If you are convinced by superforecasting, then a bunch of superforecasters claiming that existential risk from AI is far lower than you previously thought should have a huge effect on your beliefs.

So—what has happened? Have a bunch of prominent AI doomers (who tend to be rationalists) changed their mind all of a sudden, shifting their estimates to be aligned with those of the superforecasters? Not as far as I can tell. (But if you have any examples I’d love to hear from you.) If anything, people are more worried now and calling for all sorts of national and international regulation. Rationalist twitter is like walking into leftist twitter and replacing the word “capitalism” with “AI.”

What’s going on here? The FRI study is incredibly good news for the rationalists, after all. You don’t have to be nearly as worried about AI-risk anymore! There should be a proliferation of awkward Bay Area parties where everyone is talking about how relieved they are. Now they can focus all their efforts on creating shrimp utopias or trying to come up with the one decision theory to rule them all.

The biggest shift in beliefs I’ve seen came from Scott Alexander, who changed his number from 33% to 20-25%. He wrote a thoughtful, self-aware piece pointing out the problem, and then basically throws up his hands and admits it’s hard to justify his refusal to update more. As he says: “it’s the lowest I can make the mysterious-number-generating lobe of my brain go before it threatens to go on strike in protest.” Scott strikes me as one of the most open-minded, truth-oriented intellectuals out there1. If he can’t bring himself to take the superforecasters seriously enough to substantially change his estimates, it’s no surprise that no one else can.

Oddly, to anyone but a rationalist, the response of the rationalists is entirely reasonable. The superforecasters are offering arguments. The rationalists think they have better arguments. So of course they won’t change their mind. This is totally normal and is how debate works in the real world. But because rationalists assign so much credibility to superforecasting, disagreeing with them by such huge margins requires some sort of emergency epistemological taskforce. When you believe that some people have a superhuman ability to forecast the future, how on earth can you disagree with them in good conscience?

We’ve witnessed an epistemological Frankenstein: the rationalists invented a class of demi-Gods, the demi-Gods disagree with them about AI, and now the rationalists have left town, hoping the monster they created doesn’t follow. (There’s something deeply ironic about all of this, given that losing control over your own creation is quite literally the core concern of AI-doomers.)

Does superforecasting work?

So here’s a question: Do superforecasters actually display an exceptional ability to predict the future? The evidence, when examined by third parties, is surprisingly weak.

In an article for The Institute for Progress, Gavin Leech and Misha Yagudin describe how they lost confidence in superforecasting despite being initially optimistic: “[O]n reviewing the available evidence, our confidence in the ‘forecaster advantage’ took a hit.” As one example, they discuss an oft cited statistic that superforecasters perform about 30% better than domain experts. But digging into the data, Leech and Yagudin find that

The playing field is actually a bit more level than these eye-catching stats imply. A closer look at the 30% claim led us to an unpublished study that indeed describes a 35% difference – but the paper’s comparison between experts and superforecasters was not apples-to-apples: the aggregation method used for the forecasters is known to produce better results than the one used for the expert analysts. A fair comparison found a 10% advantage for the amateurs, not reaching statistical significance. (emphasis added)

Then there are concrete examples of significant world events not being assigned a high probability by superforecasters. As noted by Leech and Yagudin, forecasters assigned only a 15% chance of Russian invading Ukraine. And throughout February 2020, superforecasters put the probability that there would be more than 200,000 Covid-19 cases by March 20, 2020 at around 5%. In fact, there were more than 258,000 confirmed cases. Of course, this doesn’t mean that the superforecasters were wrong, since low probability events do in fact occur. But clearly they were caught off guard. Many other issues, including problems with the evaluation methodology, are nicely summarized by Ben Recht here.

Statistics aside, do people with skin in the game use superforecasting? After all, if superforecasting was reliable, then it would be hugely valuable to companies and governments. Do they use it?

It doesn’t seem like it. Some companies have trialed internal “prediction markets”, but a big report found that they failed to gain traction. Of course, it’s possible this is for complex sociological reasons unrelated to the efficacy of these markets, but you’ll forgive me for thinking that if a company could reliably get accurate information about the future they would figure out a way to make it work—Hansonian arguments aside. Meanwhile, the GJP website lists some case-studies that, presumably, are supposed to illustrate the benefits of superforecasting. Most, however, don’t demonstrate any concrete wins, instead simply listing forecasts that have been made or workshops that GJP has run.

One study, however, does demonstrate a success for superforecasting: a recent whitepaper about forecasting the Fed’s target range. Superforecasters were 66% more accurate (according to a Brier score) than the “CME FedWatch tool.” I have no idea what the FedWatch tool is, but it seems dishonest to not acknowledge that superforecasting worked in this case. So let’s mark this as a win on the ledger. One win among several failures still leaves me somewhere between skeptical and dubious.

In fact, superforecasters themselves seem to be skeptical of the applicability of superforecasting. Here is Michael Story acknowledging that superforecasting isn’t “immediately valuable” to people:

Forecasting might be overrated. Nearly all forecasters are paid more by their day jobs to do something other than forecasting. The market message is “don’t forecast”! Forecasting websites also don’t exactly get a huge amount of traffic, so it isn’t like huge numbers of people are relying on these forecasts to make important decisions yet. If this was immediately valuable to people, they would be looking at it all the time, and they’re not.

Alas, for now, it seems like governments still rely on people providing them with reasoned arguments, not numerical probabilities about the future. Here is Story explaining what kind of intel the UK government wanted in the early days of Covid:

During the pandemic, Dominic Cummings said some of the most useful stuff that he received and circulated in the British government was not forecasting. It was qualitative information explaining the general model of what’s going on, which enabled decision-makers to think more clearly about their options for action and the likely consequences. If you’re worried about a new disease outbreak, you don’t just want a percentage probability estimate about future case numbers, you want an explanation of how the virus is likely to spread, what you can do about it, how you can prevent it.

So what do we conclude about superforecasting? Certainly it’s not a magic bullet. If it were, we’d see a priestly class of very rich people in control of everything. But there might be some signal in the noise, however faint. This is not overly surprising. After all, much of superforecasting appears to be adhering to basic principles such as open-mindedness, changing your worldview as new information becomes available, and being open to criticism. As Tetlock puts it, superforecasters aren’t actually using Bayes’ theorem or fancy math. They’re simply willing to change their minds upon receiving new information and arguments:

The superforecasters are a numerate bunch: many know about Bayes’ theorem and could deploy it if they felt it was worth the trouble. But they rarely crunch the numbers so explicitly. What matters far more to the superforecasters than Bayes’ theorem is Bayes’ core insight of gradually getting closer to the truth by constantly updating in proportion to the weight of the evidence. Superforecasting, pg 238

It’s unsurprising that someone with epistemic humility outperforms an ideologue wedded to a single perspective. This doesn’t give you magical abilities to peer into the future, but it can make you see reality more clearly. Believing that superforecasters have unlocked the ability to pull back the veil on the future puts those that disagree with them at an impass. Unless, of course, superforecasting only works when you agree with the results?

Thanks to Cam for comments.

-

I’m basing this assessment on that weird, utterly asymmetric parasocial relationship that you have with your favorite writers and podcasters. The one where you feel you know them quite well but they haven’t spent even one second in their entire lives thinking about you. ↩︎

Subscribe to get notified about new essays.