And the Lord said to Moses, I will rain down optimization from heaven

June 17, 2023; Updated June 19, 2023

- 1. Brief recap of optimization and evolution

- 2. Evolution as optimization?

- 3. Real versus artificial worlds

- 4. Having it both ways

- 5. Optimization is not manna

I’ve been increasingly puzzled of late by analogies between evolution by natural selection (a biological phenomenon) and optimization in machine learning (a branch of mathematics). This is a particularly common trope among the small but growing contingent of people who are concerned that AI will kill us all (when, how, and why it will kill us all is unknown—but by Jove are they ever sure it will.) Eliezer Yudkowsky, a name quickly becoming interchangeable with “The Archetypal Pessimist”, repeatedly drew such analogies on both The Lunar Society and the Lex Fridman Podcast. Robert Wiblin made the analogy on twitter. Roko Mijic made similar noises on Robert Wright’s podcast.

Distraught as I am to have to disagree with this cheery lot who foresee humanity’s demise written in the stars compilers, I think the analogy between evolution and optimization obfuscates much more than it illuminates. It is occasionally helpful as an intuition pump, but should not be relied upon as the premise of detailed arguments about AI. At the very least, any such analogy needs to be argued for, not merely asserted. Something-something Hitchens and his shaving routine something-something.

Let’s take a minute to lay the groundwork for those not neck deep in vexing arguments about AI on twitter.

1. Brief recap of optimization and evolution

Evolution by natural selection involves blind variation of genes followed by the selective retention of those changes which were advantageous for the organism. Blind variation refers to the fact that the variation at the gene-level is effectively random (they are due to chance mutations or copying errors during replication). Consequently, the process is undirected: genes have no goals. They are not trying to mutate in any particular direction—they are not trying to do anything. But different genes have different effects, and different effects lead to differential rates of survival among organisms. And bada-boom bada-bing we have evolution: genes whose effects proved useful are more likely to be found in the next generation. Now simply iterate for millions and billions of years.

Mathematical optimization, meanwhile, involves … well, math. At a high level, we have some function (called a loss function) that we’re trying to minimize. If you’ll forgive the temporary intrusion of some algebra, suppose the loss function is \(f(x) = (x - 2)^2\). This function is minimized at \(x=2\) (you can convince yourself by drawing a picture, doing a little calculus, or simply noting that f will be positive everywhere except at \(x=2\) due to the square). The field of optimization focuses on developing efficient computational methods to solve these problems (this only gets interesting when the loss functions are significantly more complicated).

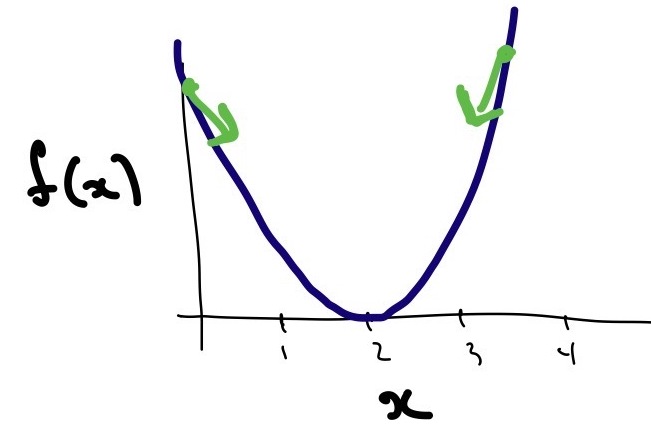

A particularly successful optimization technique is gradient descent, which is a method based on the geometry of the loss function. Imagine the function as a landscape, and consider walking downhill from wherever you begin. If you cannot walk downhill any longer, then stop. The function \(f\) above has the shape of a parabola, so it’s easy to see that this strategy will indeed eventually lead you to the minimum regardless of where you started. The same intuition holds for higher dimensional functions, although one has to imagine higher dimensional landscapes. This can be challenging without pharmaceutical intervention.

A bad hand-drawn illustration of \(f(x)=(x-2)^2\) (dark blue line). At any point, the direction of steepest descent is towards \(x=2\) (green arrows).

In machine learning, we choose the loss to measure how well the model is performing on a specific task. Roughly, it compares the true label to the predicted label and penalizes the prediction according to how wrong it is. For the much discussed large language models (LLMs), the label is simply the next word in the sequence. For instance, given the input “Harry Potter is a,” the predicted word “wizard” will score better than the word “toad.” The model is trained by minimizing the loss over training data (e.g., a bunch of text from the internet), using optimization to efficiently tweak the parameters of the model until the loss is sufficiently small. (In our example above \(x\) is the only parameter, but large neural networks have billions of parameters. Optimization tells us how to tweak each one to minimize the loss.)

2. Evolution as optimization?

Biological evolution can certainly be seen as some kind of optimization process. The accumulation of adaptive mutations over long periods of time create organisms that are especially well-suited to a given niche. Depending on the niche, this may involve gills and eyes. It may involve echolocation or the ability to photosynthesize. Or, as in the case of humans, it may involve the evolution of minds capable of art, language, and reason.

That said, there is some distance between the notions of mathematical optimization and evolution. Yudkowsky, however, recently tweeted out the following, which suggests that he—and probably the many people he’s influenced—are relying on the parallels as arguments about the inevitability and imminent arrival of artificial superintelligence.

If you optimize hard enough over any open-ended problem, you get minds; minds that want things. Minds and wanting are effective ways of computing complicated answers. That's how humans, and human brains, came into existence just from evolution hill-climbing "how to reproduce".

— Eliezer Yudkowsky (@ESYudkowsky) May 21, 2023

The claim is that because evolution by natural selection gave rise to human brains, so too can any kind of mathematical optimization provided the problem is sufficiently “open-ended.” Yudkowsky goes on to define an open-ended problem as a “complicated problem where you can go on getting better and better at it.”

Obviously, this all hinges on what exactly he means by a “complicated problem.” Consider calculating the decimal expansion of \(\pi\). You can get better and better at this; progress will never saturate because the expansion is infinite but non periodic. But a computer tasked with calculating this expansion for the next twenty billion years will not develop general intelligence.

To be fair, I’m sure Yudkowsky would take issue with this example. Perhaps he would say that this calculation isn’t sufficiently complicated. But this imprecision is all part of the problem. The AI-is-going-to-kill-everyone conversation is dominated by grandiose claims that are hard to prove wrong because they’re so vague. And then when they’re not proved wrong, an army of people on twitter begin yelling that we’re all about to die, journalists start to take them seriously, and the general public develops a severely skewed understanding of this technology. (And then, to complete the cycle, some people use this public opinion as evidence that they are correct and that they can bow out of the conversation, safe and assured in their victory. Pooh and Piglet have almost caught the woozle.)

3. Real versus artificial worlds

Machine learning takes place in a highly artificial world. We carefully select training data and structure it so that learning is possible. The goal is well-specified (minimize the loss), and so is the procedure for reaching this goal (gradient descent). The space of possible outputs is known beforehand (e.g., the set of words constituting the corpus). Models are being trained in what Jimmy Savage would call “small worlds,” which I’ve described previously as “worlds where all inputs and outputs are known, as well as the rules governing all interactions. There are no unknown unknowns.” This is why math, inductive reasoning, and probability work so well in these domains. We have crafted the artificial world such that they are useful. We have parceled the world into legible chunks, told the model which chunks are relevant, and given it a mass of examples to learn those chunks.

This artificial world is the opposite of the real world which, of course, is where natural selection occurs. This distinction is responsible for several substantial differences between mathematical optimization and genetic evolution.

3.1. What’s the loss?

If one is to analogize evolution and optimization, the first step is to identify a loss function in the former. What, exactly, is evolution optimizing? One may be tempted to say that evolution has “inclusive fitness” as a loss function, i.e., the number of descendants and close relatives that an organism shares in the next generation. But this would be misleading in several ways.

First, evolution is not goal-oriented—there is nothing it’s trying to do. It is not proceeding “in the direction of steepest descent” in the same way that gradient descent is (even if that phrase were to mean anything in the context of natural selection). Second, inclusive fitness is a more abstract notion than a mathematical loss function. It is constantly changing depending on the organism and its niche, whereas a loss function is not. Third, loss functions in machine learning include the desired output. That is, they compare the predicted output with the target output. This target output is selected by humans. Inclusive fitness has no target output; there is no superhuman figure dictating whether a genetic change was good or bad. Therefore, the means by which you’re judging progress is different in the two cases. Finally, genetic evolution is discrete (the “parameters” of the “model” are the ACGT base pairs). This is distinct from machine learning, where we choose the loss to be continuous and differentiable (mathematical properties which make the optimization process tractable).

3.2. Hardware versus software

As Quintin Pope points out, the “optimization” of natural selection and the optimization in machine learning are working at different levels. Natural selection changes our genome, which gives rise to our brain structure—what connects to what, how many connections there are, the physical shape of our brains, and so on. Optimization in machine learning takes the model architecture (typically a neural network) as given and optimizes over the parameters of the network. The number of parameters in evolution (the size of the genome) is therefore constantly changing, whereas the number of parameters is fixed in machine learning.

More generally, natural selection is an embodied process. It involves directly interacting with the world. The claim that (super)intelligence can be evolved in an artificial, digital world is not at all obvious. In fact, there is a direct conflict between evolution and optimization here: natural selection in humans first produced motor functionality and only then evolved higher cognitive capacities. (Arms and legs predate the human brain. The former evolved in Hominidae.) Machine learning is attempting to go directly for the latter. Even if you believe this is possible (which I do), the argument as to why it’s possible cannot follow evolutionary logic.

3.3. Novelty is punished

The final disanalogy comes from a personal discussion with Jacob Springer. Optimization in machine learning works, as we’ve (tediously) discussed, optimizing the parameters of a model by minimizing the prediction error over the training data. This implies that the model will be penalized for new “ideas” (sequences of words) that are not part of the training set, regardless of whether they are true or false. More precisely, it will be penalized for sequences of words whose conditional frequencies do not match those of the training set.

To make this concrete, imagine training a language model on all text prior to Galileo’s famous 1610 pamphlet. The sentence “the sun rotates around the earth” is more consistent with this corpus than the statement “the earth rotates around the sun.” A language model will thus be explicitly discouraged by its training to output the latter. It is for this reason that these models are excellent at summarizing and compressing known ideas (including code), but rubbish at generating truly novel insights which contradict the status quo.

Random genetic mutations, by contrast, do not have to be consistent with any “training data.” New phenotypes are judged only according to whether they prove advantageous at gene replication in the current environment.

4. Having it both ways

The analogy between evolution and optimization tends to be applied when convenient and ignored when not. If evolution optimized humans to be smart, then it also optimized us to be social, curious, sexual, and all the things that fit into the messy bucket labeled “human nature”. Oddly, I never seem to hear about a possible existential risk due to social, self-conscious, and status-seeking automata.

Meanwhile, we often hear the AIs will undergo some sort of recursive self-improvement. They’ll start modifying their own code, proceeding from human-level intelligence to superintelligence within a matter of months, days, or minutes. Humans, however, don’t do this. If we’re going to appeal to the equivalence of gradient descent and evolution as an argument for why deep learning will produce general intelligence, let’s at least be consistent about it. We can’t begin arbitrarily layering on abilities never seen in any organism produced by natural selection.

5. Optimization is not manna

It may seem unfair to pick on this single tweet. (I’d feel worse if its author didn’t think he was the smartest human alive. Perhaps he’ll deign to explain himself next time.) But I think this view is widely held (though perhaps not stated in these terms), and is fomenting huge amounts of confusion. For instance, the philosopher David Chalmers recently gave a talk1 in my department. One of his slides read:

An algorithm that truly minimized text prediction error (subject to constraints) would presumably require deep models of the world and genuine thought and understanding.

If so: sufficiently optimizing text prediction error in a language model should lead to world-models, thought, and understanding.

And here is Ilya Sutskever, chief scientist at OpenAI, on the Lunar Society Podcast discussing the power of next token prediction, and why being able to predict the next token well enough implies all sorts of abilities:

[W]hat does it mean to predict the next token well enough? It’s actually a much deeper question than it seems. Predicting the next token well means that you understand the underlying reality that led to the creation of that token. It’s not statistics. Like it is statistics but what is statistics? In order to understand those statistics to compress them, you need to understand what is it about the world that creates this set of statistics? And so then you say — Well, I have all those people. What is it about people that creates their behaviors? Well they have thoughts and their feelings, and they have ideas, and they do things in certain ways. All of those could be deduced from next-token prediction.

Both Chalmers and Sutskever are making the same mistake. They are treating optimization as an abstract process (truly minimized prediction error, predicting the next token well enough) and arguing about what sorts of abilities it will have. But to connect these arguments to modern machine learning, you have to argue about the actual optimization process in these systems (gradient descent or variants thereof), as well as what they’re optimizing over (structured training data selected by humans).

Alas, “optimization” is not a magical fluid that can be poured onto problems of your choosing to inexorably dissolve them. Arguments which claim insight into machine learning based on evolution are, more often than not, playing a language game. The word optimization means many different things. Simply because you can use the word optimization to describe a process does not mean that it will result in fully formed malicious minds launching themselves into the ether.

Of course, none of this is a knock down argument against AI risk (even of an existential nature). In fact, I agree there are things to be worried about. But I find the connections between optimization and evolution to be tenuous at best, and relying on such connections as arguments as to why deep learning will inevitably create superintelligence is careless.

Thanks to Vaden for comments.

-

Unfortunately this is only available with a password. If you’re interested, send me an email and I’ll give it to you. ↩︎

Subscribe to get notified about new essays.